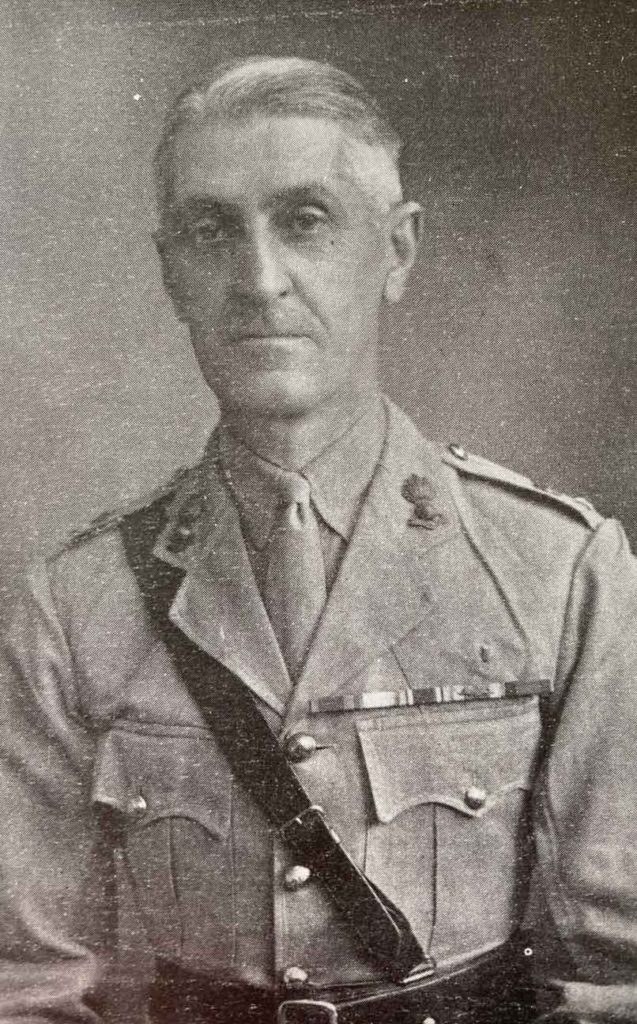

War memoir - Capt. R. Archer Houblon, 32nd Battery, R.F.A.

This is an excerpt from a memoir of Major Richard Archer Houblon D.S.O. who joined 32nd Battery, 33rd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery as a Captain in February 1915. He served as its commanding officer throughout the Somme Offensive, but was withdrawn from the front when he was badly wounded at Laventie on 18th July 1916; my grandfather William Baynham was also wounded at Laventie on that day, having joined 32nd Battery on 1st March 1916.

The memoir (‘Richard Archer Houblon, A Memoir’, compiled in 1970 by George Seaver) provides another layer of detail to the 33rd Brigade War Diary and a counterpoint to the personal war diary of Captain Tom Davison (Houblon’s second-in-command and a volunteer officer); it also offers an insight into the character of the career soldier who led 32nd Battery.

[ the square brackets are mine and I have expanded some abbreviations to assist the reader ]

Early in February [ 1915 ] he was transferred to the 32nd Battery R. F. A. of the 8th Division in preparation for the assault of Neuve Chapelle as one of the many wire-cutting batteries whose task, with their guns advanced close to the line, was to destroy the German barbed wire entanglements protecting their trenches, and clear a passage for the assaulting infantry. “It became the model on which all subsequent attacks throughout the war were based”.

In April he was selected as the gunner officer to be attached as observer to the Royal Flying Corps stationed at St. Omer devising methods of co-operating with the artillery. After a few flights he acquired the knack of quickly identifying features of the landscape which he had surveyed from the ground. And from the air he witnessed the dreadful scenes of the Second Battle of Ypres and the destruction of the Cloth Hall and Cathedral.

Early in May the Battery moved into position near Laventie for the battle of Aubers Ridge. “I had a perch in a tree a little way in front of the guns. It was a sort of ship’s painter’s chair in which one was hauled up by a rope previously shot up into the branches by means of a grenade fired from a rifle”. On the 9th, whilst running across a ploughed field to some gun-teams heading along a direct road in full view of the enemy, he was knocked spinning by the burst of a shell behind him and was “so dazed and shaken that I remember little of what happened afterwards except that we somehow got the teams reversed”. It was in fact a case of delayed concussion (his second), and from the effects of it he never fully recovered but was subjected intermittently for the rest of his life to very severe headaches about which, as General Goschen says, he never complained but which were sometimes a torment to him.

The Battery moved the same evening back to Laventie, “but I remember very little of the next two or three weeks.” He was invalided home at a time when all leave was stopped. “I must have been the only regimental officer on leave from France at that time!”

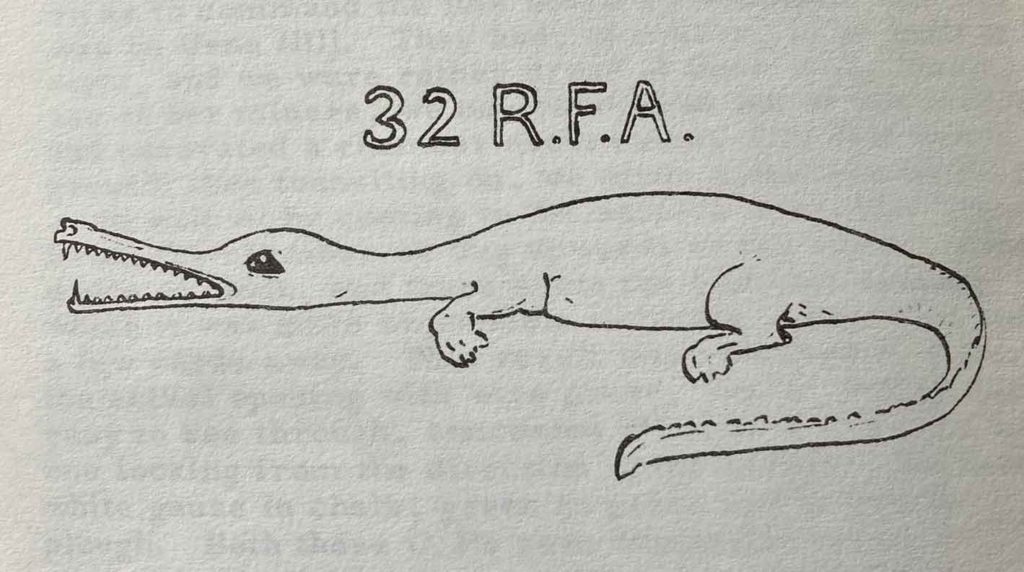

Returning in mid-June he was put in command of the Brigade ammunition column; then appointed adjutant; and soon after, though not yet of Field rank, given command of the entire Battery. It was still composed very largely of reservists many of whom had marched with Kitchener to Khartoum. “So I racked my brains to think of something that would capture their imagination and eventually drew a fierce-looking crocodile for use as a Battery sign, stencilled on to every gun and wagon. After that they quite forgot about their old units and really did become 32nd Battery men.”

His disposition of the Battery for the battle of Loos on 25th September was so skilfully screened from view in the Bois Grenier that, though the wood was persistently shelled, there were no casualties. The whole Division went into rest at the end of November, after nearly a year in action, and “the relief at being able to undress and go to bed without the likelihood of having to rush out and answer an S. O. S. was indescribable.” On the night of 11th January 1916 they were in action near Fleurbaix; and Dick erected an Observation Post in the gable end of a shelled cottage overlooking the enemy front trench. “Suddenly a German gun swung across and like lightning put five direct hits through our wall, sending us down head first on top of the astonished telephonist below, in clouds of brick dust, chips and smoke.”

With the coming of spring the Battery joined the first Cavalry Brigade and marched south by easy stages to the Somme. “The first march took us to Franvilliers; it was a fine day and the Battery was turned out quite well, so much so that a strange general who passed us wrote to the colonel of our brigade to say how much he had been impressed!” They spent ‘some wonderful days’ at La Chausée, and all ranks from the trumpeter upwards made expeditions to Amiens ‘where the shops were still gay and plentiful’. Thence, in early April, to the outskirts of Albert – and two hearty welcomes for the British soldiers from its inhabitants who ‘later on hated having Americans and positively dreaded having Italians and Portuguese’. The men collected plants from some deserted gardens and each subsection made a garden round its pit. This evoked the admiration of passers-by, and a bright young subaltern was heard to exclaim: “I say, isn’t this a perfectly priceless battery!”

Then on to Bécourt Wood with a view over a long section of the German lines and no less than seven villages, and ‘great blazes of scarlet poppies, yellow mustard, blue cornflowers, and rich crimson clover in the open sun-bathed fields … so like our beautiful Berkshire Downs. One pair of partridges hatched out twelve eggs within two feet of the deep wire trench we dug to the Observation point. Another bird produced a brood at Crucifix Corner, a spot that rarely passed two hours without being visited by at least one shell’. Shrikes and woodpeckers as well as many strangers could be seen and heard and the Ancre was full of trout. In flooded tracts of the meadow-lands ‘the sole effect of a German bombardment was that the men had trout for dinner’.

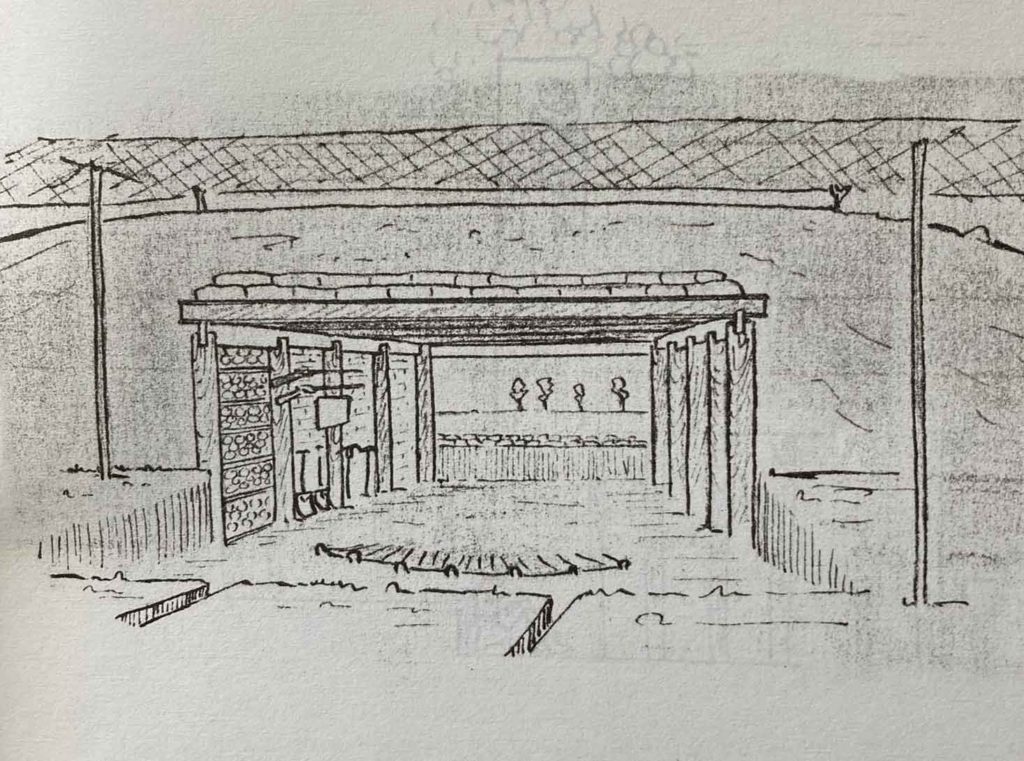

A gun position was prepared near Crucifix Corner, and here Dick devised deep gun-pits which excited first the envy, and afterwards the emulation, of other Field Artillery Batteries. “These pits were built nine feet wide; a greater width would have been more convenient, but in this case the width had to depend on the length of the girders available for supporting the roof. The pits were sunk two and a half feet into the ground. Five eight-inch pit props on each side supported the girders of the roof. About five feet of chalk was heaped on the roof, with a layer of flints one foot from the top to form a ‘burster’ which was to ensure that shells dropping on the pit burst before they had time to penetrate very far into the chalk. Powdered bricks made a good hard floor, or ‘platform’ in technical language. In the pit, as shown in the sketch, were shelves taking three hundred rounds of ammunition, all sorted and labelled into different types of shrapnel and high explosives. Rifles for local defence, picks and shovels for digging a way out in the event of a shell blocking the pit, notice boards with instructions and information for the firing, and spare gas helmets, were hung on the walls.

Inside the pit there were also buckets of water and ‘sponges’ for keeping the guns cool during heavy firing. On the right-hand side of the particular pit illustrated, there was an entrance to a dug-out for the detachment. When the gun had been put into position inside, the back was closed up by building a ‘parados’, or wall of sandbags. In front of the mouth of the pit, called the ‘embrasure’, we dug holes to act as shell traps, the idea being that shells falling just in front of the pit would burst in the hole and be smothered, instead of sweeping with its fragments the whole interior of the pit. When the guns were not firing, screens were put up in front of the embrasures, to prevent their showing up as a row of black marks to an airman over the German lines. The whole pit had a camouflage net supported on poles spread flat like a canopy over it. This made it invisible to any airman who might be examining the country from above.

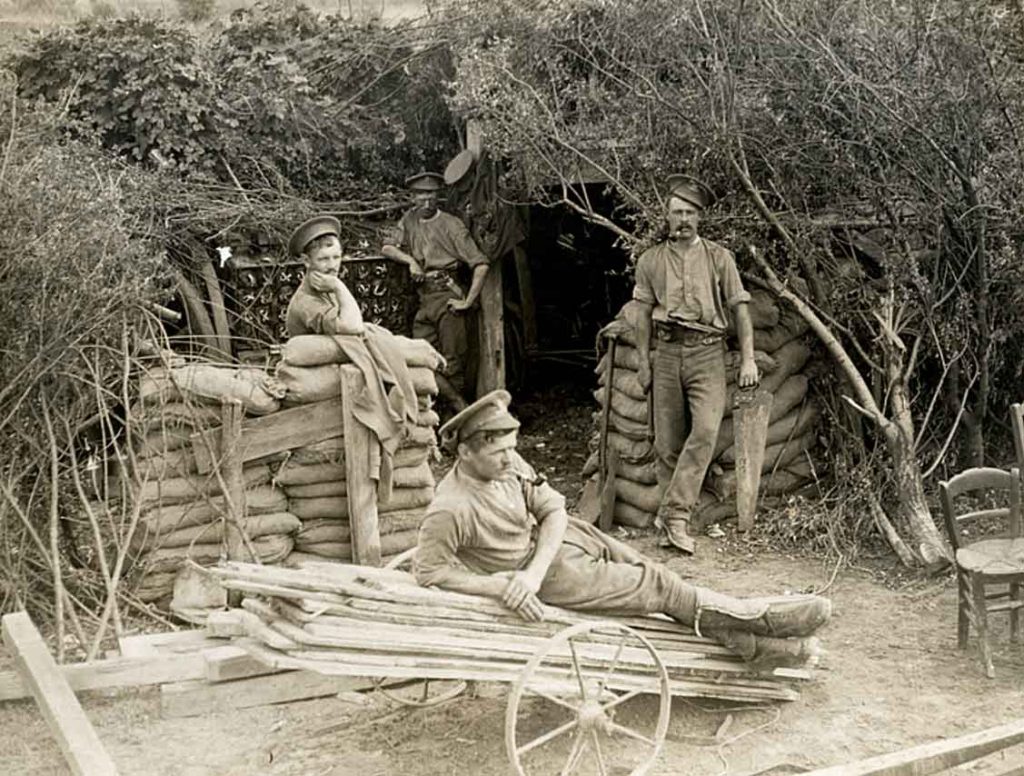

This photograph was taken by H. D. Girdwood, on 4th August 1915. He said that it was a scene in a battery at the front, at Lavantie, but this may be incorrect as many of his photographs were staged for propaganda purposes. However, it does have several of the features of a ‘Dick Houblon’ gun pit.

“As soon as the position was sufficiently advanced to afford some accommodation we began to move, and the plan adopted – the whole divisional artillery was involved – entailed one of our sections and one section of another battery occupying the position jointly for two or three nights.“

At La Boiselle, ‘the home of every horror known to trench warfare’, including tear-gas shells, and where two lines almost met in a disrupted minefield so that it was difficult to know whose trench one was in, he caused tunnelled Observation Posts to be constructed.

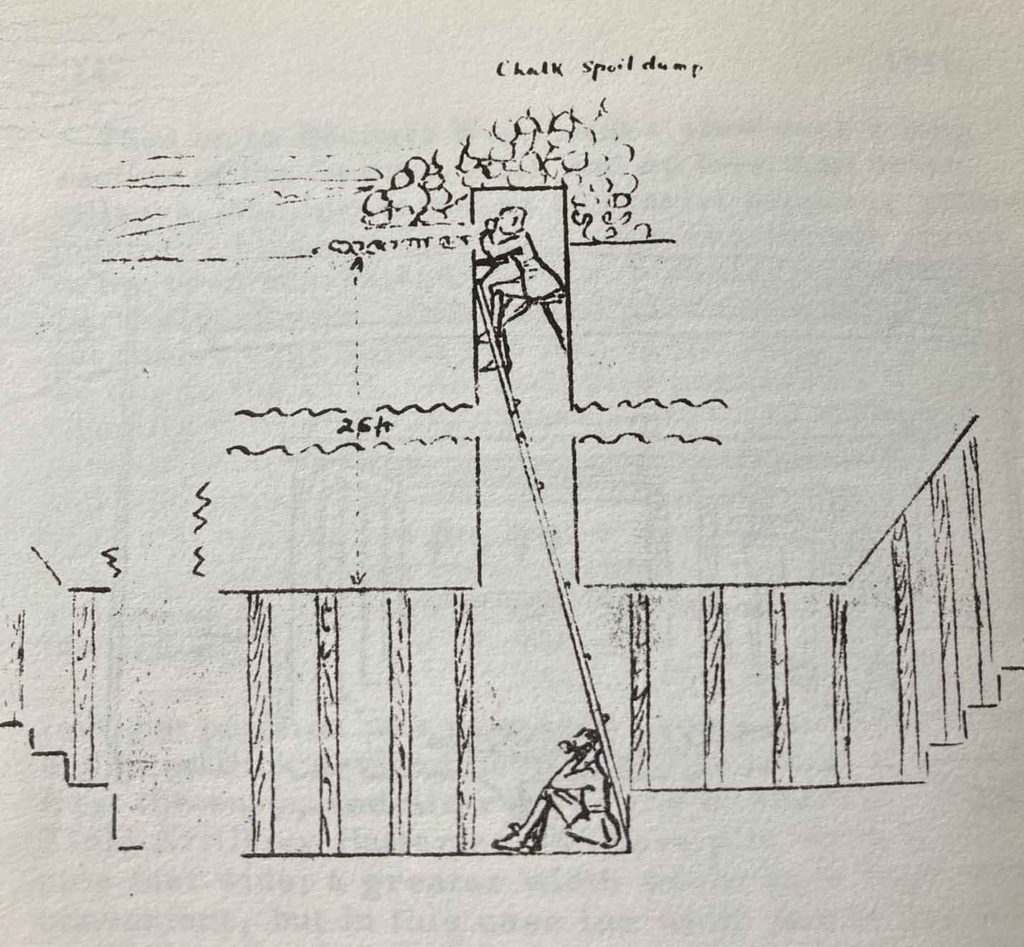

“We built two Observation Posts for our battle position, both in support trenches. One looked into Ovillers and north as far as Thiepval, and the other faced more south, so as to command the line below La Boiselle; this one was on Usna Hill. They had, of course, to be built at night, and we were rather proud of them both. Making use of our miners, we tunnelled down out of one trench and excavated a chamber about twenty-five below ground; then tunnelling on, we made a reserve entrance – or exit – by coming to the surface in another trench. From the chamber we dug upwards to the surface under a pile of chalk, and there made the look-out opening which it was quite impossible to locate, even from only a few yards away. This result was achieved by covering the actual opening with wire gauze, which, though quite easy to see through, concealed all sign of a hole to anyone looking from the direction of the enemy. We used white gauze in chalk, green in grass and brown in plough. Both these Observation Posts gave wonderful views.“

Among the junior officers on the strength of the Battery since January of that year was a second-lieutenant recently commissioned from private life, whose impressions of its commander, both at rest and in action, are a valuable contribution to this memoir:

Mr. F. E. Frith, M.C., writes:

“I can claim no place in his circle of personal friends; our paths ran together for a bare six months, more than half a century ago, but I do not forget him, for he was a man I very much admired and respected, and I owe him a debt because I have felt ever since that his example and his standards and the way he tackled his duties and responsibilities set a sort of pattern which I have always taken as a good one to try and follow in everyday life.

“I was very much a ‘new boy’ when I joined the 32nd Battery and wondered how I should get on with this – as I had been told – rather formidable C.O. My first impression was indeed of a rather severe-looking and aloof-seeming officer, but I soon found that, although he could administer a searing rebuke when needful, he was always most fair and just, and very helpful and friendly as long as one was trying to do one’s best, and was also entirely ‘one of us’.

I was so much impressed by his tremendous thoroughness and his concentration on efficiency, his attention to detail, his care for his men and horses, his guns and harness, and everything connected with his Battery. He knew, or had discovered, that it had distinguished itself at Omdurman, and resolved that it should be known as the ‘Crocodile Troop’ – a very nice touch, we thought, and good for morale. I wondered sometimes whether, as a Horse Gunner, he had regrets at only having a Field Battery; but he had the distinction of being still of Captain’s rank while all the other R. F. A. Battery Commanders were Majors.

“He was always perfectly turned out, and always punctilious. In quieter times, after we had dined whether in dug-out or billet, his personal servant would, almost ceremonially, bring a little mahogany smoker’s cabinet, and he would fill and smoke his one pipe of the day – a notable example of controlled smoking. In quieter times too, when the Division was resting in the back areas, he would scour the neighbourhood for a field or a bit of country large enough for full-scale Battery drill and exercises, with an eye no doubt on the hoped-for time when there would be a real advance and returned to open warfare more in real Horse Artillery style.“

In preparation for the battle of the Somme, the Battery was linked to another Division for ‘wire-cutting’ in the Fauquissant area near Laventie. The position allotted to it was almost completely in the open and the enemy had already found the range. The distance to the hostile wire was so short that shells required a flat trajectory and screen from view was impossible. On 16th July the Battery opened fire and the German guns replied immediately. They quickly scored direct hits on two guns. Ammunition had been deposited in dumps here and there; some of these were now hit and exploded. Another pile of reserve ammunition had been stored in an old thatched cottage about thirty yards behind the line of guns. Two or three enemy shells dropped into it and fired the thatch and soon afterwards caused some of our reserve stock of shells to explode. Communication between the Observation Post and the Battery was also broken and Houblon returned to the gun position in order (as he puts it) ‘to re-organise’. What this involved he does not say, but Mr Frith’s memories are revealing:

“I recall his ability to make instant, firm, and correct decisions in any sort of crisis, and his coolness under fire. I clearly remember the sight of him, on a day in July 1916, walking up and down behind the guns amid a shuttering racket of German 5.9 ‘crumps’ and crashing treetops, with our guns cracking away handsomely through it all. One after another the other two were put out of action and casualties were mounting.

“Not far behind the guns was a small dilapidated thatched barn and our reserve of ammunition had been put into it. The Germans were dropping odd shells around the area for annoyance purposes, and just before we were to start the wire-cutting operation one of these set fire to the thatch and flaming fragments began falling inside. Needless to say, it was Houblon who was first on the spot and I can see him now dashing into the smoky barn and emerging unconcernedly with a round in each hand, * seeming to know that every man available would follow, and then directing the rescue procedure so that it should be done in proper orderly fashion and with no confusion. Then he himself was hit; our line to the Observation Post was cut and we were blind.” All that he says himself about this is: “Just as I got back to the guns one of the last German shells sent a splinter into my hand.”

* They were eighteen-pounders. A clip was attached to the base of each cartridge case, gripping the rim at four points and covering the cap, and having fixed to it a canvas loop. This protected the cap from any accidental blow; the loop made it easy to pull out the round from its compartment in the limbers and ammunition waggons; and also provided a handle to carry the round from one place to another.

The enemy had ceased fire and there was a temporary lull. In the afternoon Hublon reopened fire, and received similar retaliation. “This time the enemy tried violent bursts of gun-fire and salvoes instead of the more deliberate fire of the morning, and blew up a number of more dumps and hit many men. But by the time we had again to stop and refit, the wire was beginning to look well cut and the German parapets were much knocked about and damaged. The men had been laying perfectly all day.” – Orders now came to postpone the attack and Houblon went at once to Brigade Headquarters “and enlightened them as to our thoughts and opinions, and demanded the allotment of a better position.” The position offered – although also shelled out – was accepted on the grounds that “it could not be worse and might conceivably be better”. Since the Germans were now firing irregular salvos to catch any salvage parties, preparations to move would be expensive; but the dawns had recently broken in mist, so Houblon decided to wait for dawn on the 17th, and took up his new position without incident. The rest of the day was spent in digging as much protection as was possible.

On the 18th he recommenced the bombardment and once again received severe retaliation, but the guns continued to fire steadily. Casualties however became so heavy that he gave orders to cease fire while detachments were reorganised. The shooting had been so good that he felt sure another hour’s firing would complete the task. The last hour proved the worst: men were being paralysed from shock; but all who could stand kept up the fire until it was certain that “the wire was well and truly cut … Personally, during this hour I got two splinters through my clothes and one large piece in my thigh, the last in a particularly bad moment when a shell dropped into the very mouth of Sergeant King’s gun-pit and killed every one of his men and laid them out for dead. It was just at this moment that Gilbert sent through to say that every sign of the German wire had been removed.”

And with that our knowledge of what he tersely calls ‘The Affair of Fauquissant’ would have ended, but for Mr Frith’s memories:

“He gave the order to cease firing and the men to retire to a flank taking the wounded. Entirely ignoring his own wound – a large piece of splinter in his thigh – he took another look round and found that one of the men beside one of the guns (a sergeant whose name I forget but I remember the weight of him) was alive though very badly wounded and unconscious. Houblon had had me with him for this particular shoot and he and I were then the only two on the scene. He said ‘We must get him out of this’ and took his legs, telling me to take him by the shoulders. We managed to get a little distance and providentially the enemy also stopped firing, so I called out to him that I would go off and get a relief party. It could not have been more than five minutes at the most, and when I got back with the relief party I think he was still there, though I’m not positively certain. At any rate I missed him after that; and when I was free to find him he had been taken away. What a man! I thought, and still think. I did not see him again.

“On my next leave I tried to get in touch with him but failed; and in later years I did not like to presume on what must have been to him a very insignificant association. But in those few war-time months I came very greatly to admire him, and I learned from his character and example lessons that have profited me through the rest of my life. To this day the memory of him stands out in my mind much more vividly than that of any other man I have had to do with in all my life.”

On 22nd September 1916 the London Gazette announced:

D. S. O.

Captain Richard Archer Houblon.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion during operations. He was wounded when wire-cutting under heavy shellfire, but stuck to his duty till two days later when he was again seriously wounded. He has always shown great calmness and bravery.

Near Laventie.

16th July 1916.

Meanwhile he had been moved by wheel stretcher to an ambulance and then by rail in painful stages to Bologna and then “at last to the intense ease and joy and comfort of a ship.” He found his cousins Muriel and Lilian Bowes-Lyon at the Royal Free Hospital working as V. A. D’s, and a little later was moved to his aunt Lady Amy Meynell’s hospital in Lennox Gardens where his sister Elsie was secretary.

“At first it was wonderful being at home in comfort and safety; but as soon as I began to recover I began to get restless and ill at ease … and before long these feelings became almost intolerable. Not that I mean to imply that the normal person likes war … but that, while sympathising deeply with those who are tried beyond their capacity, anyone who has ever worn a uniform and learned what comradeship means, feels that if there HAS to be a war, then he MUST be in it, and cannot bear to hear of others going through it without taking his share.“

He was promoted Major on 30th November 1916.

When at last released for light duty he was sent first to the reserve brigade at Woolwich and thence to the H. Q. of the London District for staff work. “I soon got intensely to dislike this office work, and at last by skilful reconnaissance of the board room, and a careful utilisation of chairs and tables as supports in going in and out, I got passed fit.”

He returned to France in February 1917 to take command of ‘ I ‘ Troop (‘Bull’s Troop), Royal Horse Artillery of which he says “Curiously enough, in the early days when I first determined to be a soldier, it was the story of Norman Ramsey’s exploit at the battle of Fuentes d’Onoro * that fired my imagination and made me ambitious to command a troop of horse artillery, and lo! here I was going up to command the very troop that Norman Ramsey had led.” This opened a new chapter which established him, as Major-General Sir Neville Swiney later wrote, as “the finest Battery Commander in World War 1, (or indeed in any war!)” and, because he had no ambition for promotion, his was one of the longest tenures of command.

He retired from the army in 1929 and died in 1957.

[ * There are numerous depictions of the escape of Captain Norman Ramsay with the two guns of Bull’s Troop at the Battle of Fuentes d’Onoro ]

Notes:

Memoir of Major Houblon, including photographs – ‘Richard Archer Houblon, A Memoir’ complied by George Seaver. First published July 1970 (Copyright Doreen Archer Houblon, 1970)

Additional photographs –

- Battery at the front, Laventie – WikiMedia Commons