War diary - Capt. T. H. Davison, 32nd Battery, R.F.A.

This is an excerpt from the personal war diary of Major Thomas Henry Davison M.C. who joined 32nd Battery, 33rd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery as a Captain on 19th December 1915 at Blaringhem. He served as its second-in-command throughout the Somme Offensive and took over as its commanding officer when Captain R. Archer Houblon was badly wounded at Laventie on 18th July 1916; my grandfather William Baynham was also wounded on that day, having joined 32nd Battery on 1st March 1916.

The diary, which appears to have been written in 1921, provides a compelling insight into the life of a volunteer officer serving as second-in-command of an RFA battery at the front in 1916 and reveals a unit of officers and men who got on well together and survived pretty much unscathed until the heavy German shelling at Laventie. It also offers a counterpoint to the memoir of his commanding officer, Dick Houblon who was a career soldier.

[ the square brackets are mine and I have removed capitalisations and expanded some abbreviations to assist the reader ]

1915, December

8th – As soon as the train stopped [ at Steenbecque ] I got out but could see no sign of Richards. I just had time to drag my valise out of the luggage car when the train moved on to Hagenbrouck [ now Hagenbroek, in Belgium ].

Now I had lost batman, groom, horse [ ? ] and some of my kit, and was alone in a strange part of the world with no idea whatever where to find the 8th Division. The Railway transport Officer “thought” they were about four or five miles away but seemed hazy as to the direction. A min [poor] look-out with night coming on.

I walked to the village and saw rows of motors [ ? ] and muster lorries which turned out to be the 8th Divisional Train. To one of their officers I told my sad story and he took compassion on me. A car was brought round and we started for Lynde (Haz 4 F) [ the Hazebrouck map, with co-ordinates for Lynde], the HQ of the 8th Divisional Artillery. I reported here and was told to go to the 32nd Battery for that night. The Staff Captain (Duncan) also informed me that the Division was “resting” but would start manoeuvres on the Monday.

My friend of the motor-car there took me another mile or so to a farm-house where the 32nd Bty officers were living.

Capt. Houblon [ Richard Archer Houblon ], the Battery Commander was having a bath, 2nd Lts. Simmons & Wallace were sitting in deep chairs in front of the fire. They welcomed me warmly but I felt an intruder. Later, Lt. Stanford the senior subaltern and 2nd Lt. Gilbert, attached from the Divisional Ammunition Column came in. I felt surrounded by regular officers who knew the form from A – Z but I was wrong. Houblon & Stanford were the only pre-war regulars. Simmons had become a regular during the War, and the others were Special Reserve.

That night I slept in the mess on the floor and was thankful that I had rescued my valise.

I found Richards wandering about aimlessly the next morning. He had gone on to Hagenbrouck and, when getting out of the train, picked up the wrong haversack leaving mine with revolver, artillery protractors, etc behind. I lost everything but in the exchange Richards got a clean set of underclothing belonging to a Sergeant.

The manoeuvres (Haz 4&5 D and Haz 4&5 F) were dull and chiefly for the benefit of the Staff who had a lot to learn. When we returned to camp some four days later I found Butcher and “Jumbo” comfortably installed.

25th – Then Christmas day came and I thought of the old battery, C/84 [ ‘C’ Battery, 84th Howitzer Brigade – his previous unit ]. Simmons was Mess Secretary and had muddled our Christmas order. As he was just going on leave it mattered little to him.

Our Christmas dinner consisted of Army Rations with the addition of 2 partridges that had been sent to Stanford. I took over the Mess Secretary’s work and we made up for it on New Year’s Day with a sucking-pig and other good things.

1916, January

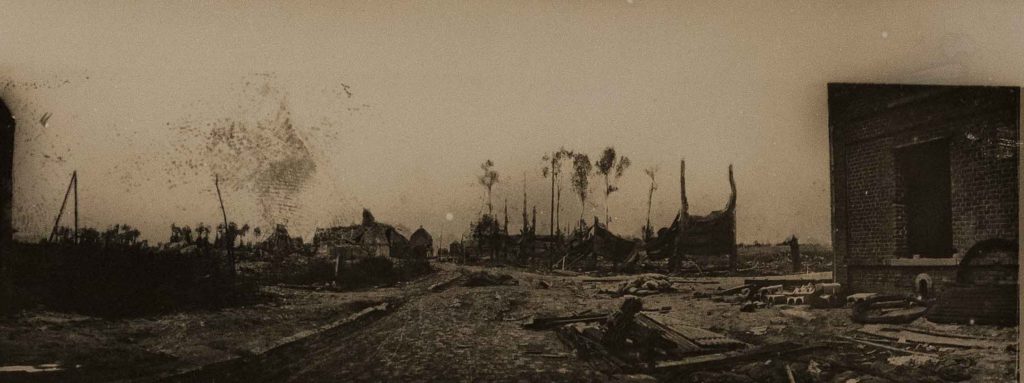

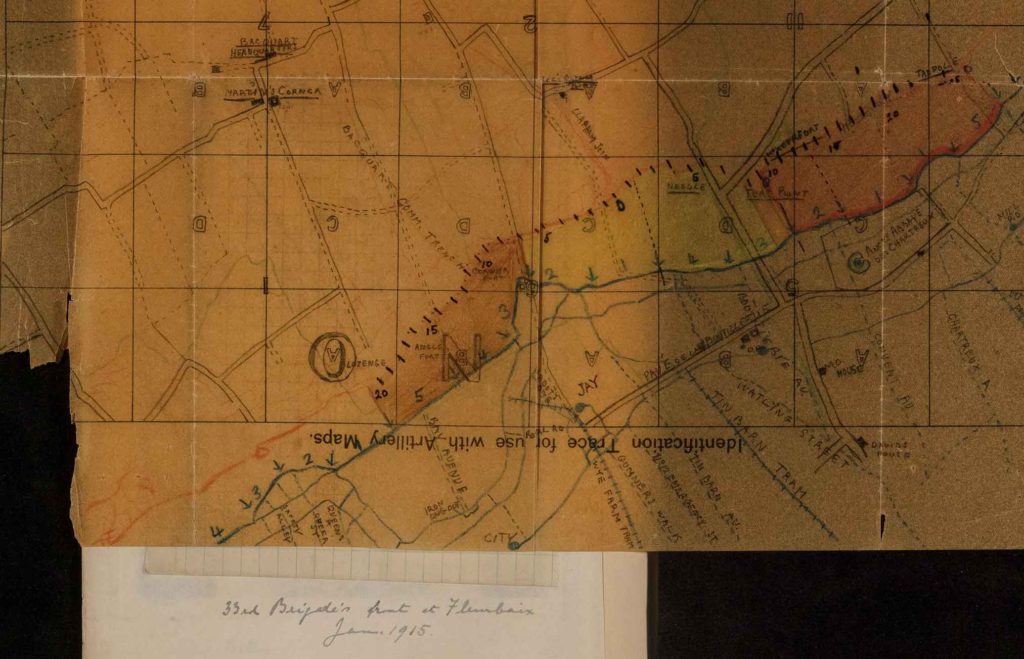

Early in the new year we marched from Blaringhem, through the north of Steenbecque, the Foret de Nieppe to Estaires where we billetted for the night, and on to Fleurbaix the next day. The battery position was in the orchard of a farm house.

The men were in the barns and the officers had most of the house. The rest was occupied by the farmer and his family. They were compensated for the risks they ran by the amount of coffee, beer and fried potatoes they sold to the men, which was very considerable. The Wagon Lines were at Bac St. Maur.

Capt. Packe of the 33rd Battery shared my billet. The house belonged to an old woman named Madame Dubec who lived with her brother or husband. I never found out which because she always referred to him as “Le Vieux” [ “The Old Man” ].

I went on leave again from here, which was very lucky. Except for occasional raids on both sides the front was very quiet. Our Observation Point was in an old ruined farm-house at La Boutillerie and we used to look through the rafters over the German lines.

For night firing Houblon had instituted a hunting-horn to call the men out. It fell to my lot to command the battery while he went away on a conference for a week. One night we got a sudden call for retaliation. I seized the horn and ran out into the yard but try as I would I could not produce a single sound out of the beastly thing. Nothing but blasts of air. This caused so much amusement amongst the other officers that matters were still further delayed.

1916, April

We remained at Fleurbaix until April and were then told that we were for the Somme.

When the day came Houblon gave me orders to have all the ammunition wagons hooked in and lined up in the road ready for the guns to fall in in their proper places. I did this but unfortunately had them facing the wrong way, in a narrow road. I had read the orders wrong and Houblon was naturally furious. The I had to reverse the twelve ammunition wagons, General Service Wagon and Mess Cart. The former and latter were easy enough, but the General Service Wagon, always heavily loaded, slid gently and peacefully into a deep ditch. I never caught up the battery again till after they had arrived at Bleu (Haz 4 I). Mine was not the only trouble. Poor old Gilbert had deposited one of his guns in a ditch also.

At 1 a.m. that morning Houblon forgiven us, as he always did, and we were all sitting round hot cocoa and biscuits.

They kept us at Bleu one night and on the following night, again in pitch darkness, we marched to Merville (Haz 5 H) and entrained. We remained in the train till 3 p.m. the following day and then detrained at Longeau (Amiens 2 E). What a difference from 9 months before when everything seemed so very strange. I felt now as if I had been in the Army for years. We watered the horses in the same place and took the same roads till just past the station in Amiens. Instead of turning North we went straight on to the West. It had been fairly fine up to now but the sky became overcast and suddenly a most awful driving blizzard started. Ice cold, and stinging against one’s face.

Fortunately for me Houblon suggested that I should ride on to our billets and do what I could. La Chausee (Amiens 1 B) [ the Amiens map, with co-ordinates for La Chausee] was the place, a pretty little village almost on the banks of the Somme. Before I had gone very far the sun came out and by the time I arrived it was pleasantly warm. It seemed like coming out of Winter in Amiens to Spring in the country.

The battery arrived about two hours later. We had quite good billets for officers and men and quite good horse lines. Everybody seemed to cheer up with the fine weather.

While we were here Houblon, Packe and myself took the train from Picquigny (Amiens 1 B) to Amiens with the object of having a good lunch, making a few purchases and seeing the town. We chose the Hotel du Rhin, at that time the last place. We really treated this lunch seriously for we were all inclined to be “gourmets”. The head-waiter was summoned and we discussed foods from every point of view till finally the following menu was decided:

Hors d’ouvres, as only the French can produce; Homard americaine; poussins rotis; salade; pommes nouvelles et petits pois; asperges; fraises au vin blanc et liqueur; with all this a delicious white wine. Then coffee, liqueurs and cigars. I don’t think one of us will ever forget that day. The novelty of it after being in the line so long, and the exhilarating Spring air, the bustle in the restaurant all added to our enjoyment.

Life at La Chausee was too good to last and we started our move for the line, a two days’ march. From La Chausee we went through St. Vast, Bertangles, Coisy (my first billet in France with C/84), St. Gratien, Frechencourt (all Amiens 1C, D & F) to Franvillers (Amiens 1 G) where we halted for the night. Here Captain Packe was ordered to take command of 33rd Battery as Major Russell was leaving to become Brigade Major in another Division.

From Franvillers we marched to wagon lines at Lavieville (Amiens 1 G) arriving late in the afternoon. As soon as the horses had been watered the guns were taken up to Albert and came into action in a position just to the right of Albert cemetery. Brigade Headquarters were in two Armstrong huts at the Western end of Meaulte, near the Moulin de Vicaries (?). In Lavieville I found an empty farm house and there I went with Richards, Butcher and Jumbo. One morning, while Butler and Richards were away for a moment, “Jumbo” walked into the kitchen and ate my breakfast off the plate. The wagon lines remained here for some time but the guns shifted as soon as we had built a new position. The gun line officers in the Cemetery position were also billeted in a house. The owners, an engineer and his wife, had defected leaving this house almost intact.

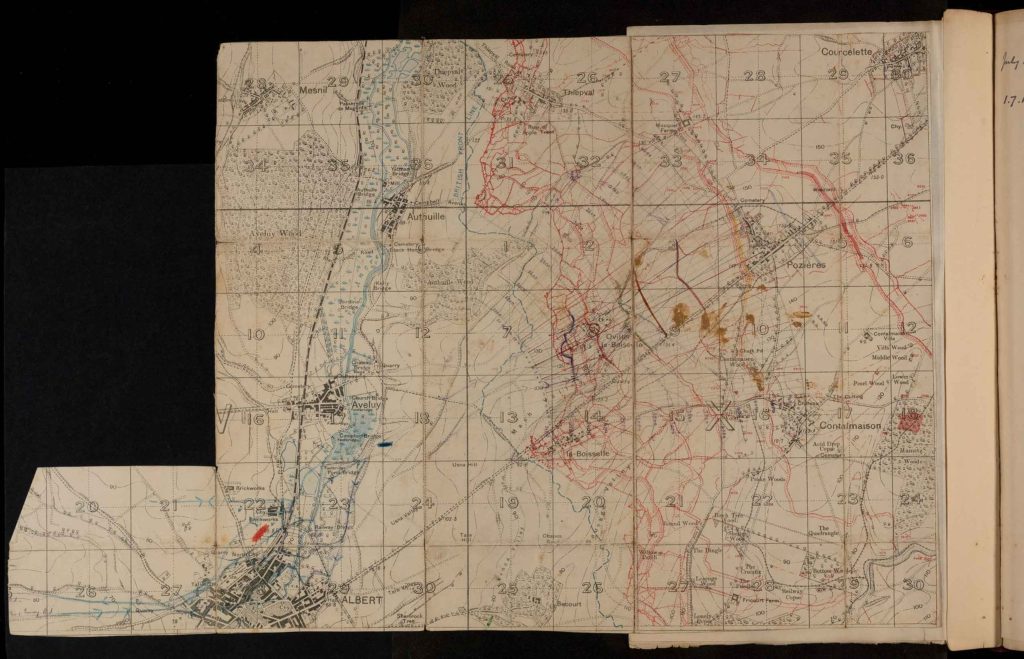

The new position was just east of Aveluy (Lens 6 I) [ the Lens map, with co-ordinates for Aveluy] with Mouquet Farm, one of the targets, on the left front (X 18 c 0.5).

In the Mess we had a message in the shape of a black cat. On the eve of the battle, while we were having dinner, she produced three kittens. We took this as a sign of good luck for the next day, but it never came off.

Each field battery had a front similar to ours, about 250 yards. The “heavies” according to size had larger fronts. This, all in addition to trench mortars, Lewis guns, machine guns and rifles. Firing was kept up almost incessantly night and day. Our battery fired something like 20,000 rounds from about the 23rd June till mid-night on 2nd July. This will give some idea of the amount of ammunition expended during the first days of the First Battle of the Somme, taking the little front as being between ten and twelve miles in extent.

1916, May

Behind the position, some 500 yards away, the river Ancre ran North & South. In places the banks had been destroyed by shell fire causing a huge lake (Lens 6 H) to be formed. The Germans used occasionally to drop heavy shells into this lake killing the fish. Our mess-cook, one day, went out on a raft and collected a big dishful for our dinner.

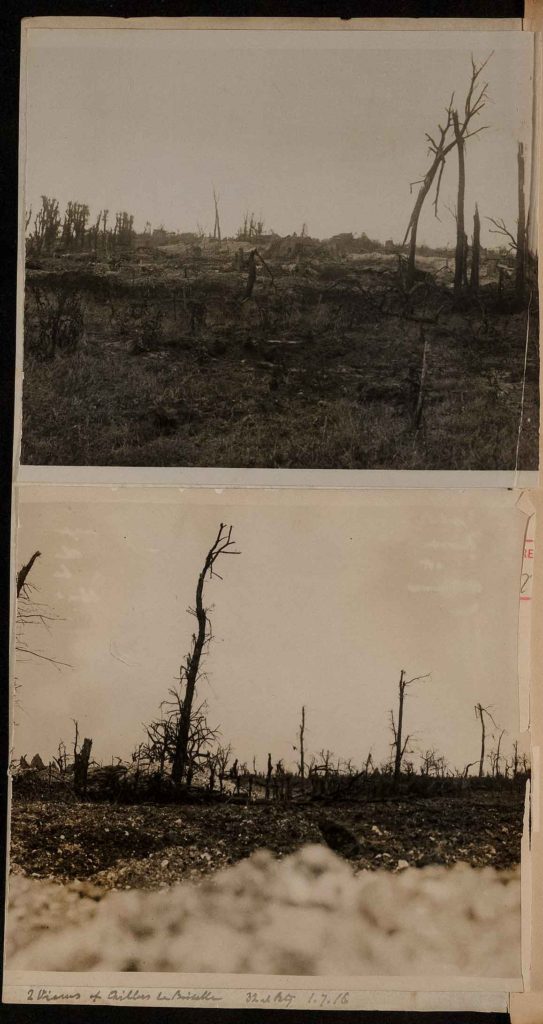

Now began all the preparations for the First Battle of the Somme. Our immediate front was opposite Ovillers la Boiselle and just to the right of this village, or what remained of it.

Observation Posts were most necessary and had to be built. We constructed two in the trenches, one for a frontal view and the other for oblique observation.

Work all had to be done at night. A deep dug out was made just off the main track and from this a shaft leading upwards with a little shelter just behind the parados of the tunnel, through which a fresse rather like a large letter box was let in, enabling one to see the enemy front without hindrance. The other Observation Post was constructed in a similar way, though deeper [ the design was conceived by Houblon and there is a sketch and a more detailed description of the construction here ].

At the gun line accesses and shelters were made to hold hundreds of rounds of ammunition [ again, the design was conceived by Houblon and there is a sketch and a more detailed description of the construction here ]. Provision was also made for plenty of drinking water and water for cooling the guns. Extra rations were also stored nearby. Every effort was made to assure communication in the event of the wires being cut.

1916, June

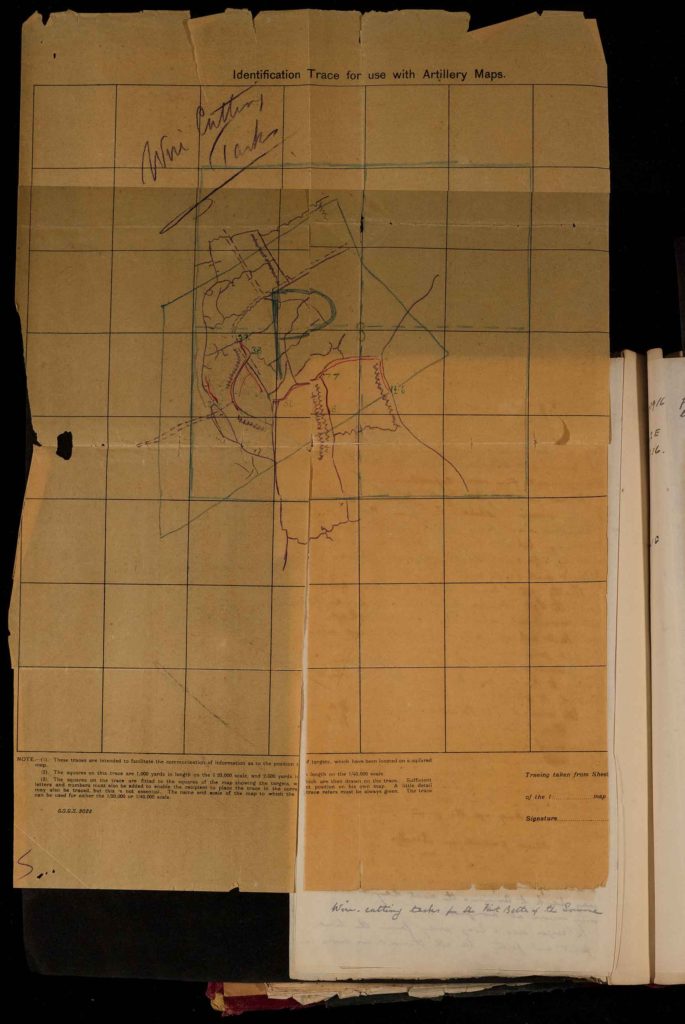

About the middle of June orders for wire-cutting and the preliminary bombardment began to come in.

Houblon was detailed as Liaison Officer between the Infantry Brigade HQ and our own Brigade HQ. This left me responsible for the working out of all the angles for the guns, but Stanford, Gilbert and Frith all helped (Wallace left us at Fleurbaix & Frith joined). Houblon’s experience and advice were invaluable to us when he was with us in the evenings.

Our Mess was in a small cutting to the left of the guns, dug into the side of one of the banks with the kitchen just beyond, similarly constructed. After dark sudden bursts of machine gun bullets would come past the door making it rather uncomfortable for the mess servants coming with our dinner from the kitchen.

Every possible preparation was made for an advance. It was the Artillery’s work to place bridges over curtain trenches between the gun positions and the front line. All Officers & NCOs went down this track at night so as to make no mistake when the day came. So certain men were of an advance [ ? ] that one officer, Frith, turned up in spurs on the morning of the attack.

Shortly before the preliminary bombardment started Stanford found a partridge sitting on a nest of eggs barely 100 yards in front of our guns. Though firing continued day and night this bird hatched out all her eggs a day or two before the battle.

1916, July

1st – On the day of the battle I arranged to be in the Observation Post with the telephonists, before day-break. As soon as I looked out I saw there was a very thick mist. This must have been about 4.30 a.m. The German front line was invisible and I could hardly see our Support Line. Zero Hour was, I believe, at 6 a.m. Up to this time there was almost silence, the mist dulling the occasional rifle shots. Then, on the stroke of time, artillery, all along the line, crashed out on the German front line for some two minutes. At the same moment German machine guns opened fire on our lines, seemingly in hundreds. When our guns opened fire the huge mine under La Boiselle, a little to the right, exploded and, even where I was, the ground seemed to rock.

In the mist I could just see our men climbing out of the support trench. It looked as if some of them hesitated and then slid back into the trench. In reality they were being knocked over by the German machine gun fire. What happened to those who got further remained to be seen when the mist lifted. By this time our artillery fire had lifted to longer ranges under the presumption that our men were advancing.

I was continually being rung up from the battery asking for information for the Brigade HQ. I could see nothing except the very heavy machine gun fire.

What had happened was that as soon as our own artillery had lifted from their front line the Germans had come up from their very deep dug outs and mounted countless machine guns.

As the mist lifted I had my first view of a battlefield. First our own front-line, then a great many dark objects which gradually formed themselves into dead men. Next I saw the German front line and slowly their other trenches came into view. When it became quite light it was clear that, if our men had got across on this part of the line, it was at tremendous cost. Dead and wounded men were lying everywhere in “No Man’s Land” and even hanging in the German wire on the other side. The telephone wires from the front line had all been cut in the first few minutes so I could get no information from there, nor could I give any.

From a lecture I heard later the Germans did not expect the attack to the South of us and had put all their strength in from La Boiselle up towards Thiepval and beyond.

By and by a message came through from Houblon to bring our fire right back on to the German front-line which proved that the attack here had failed. A little later Houblon himself came up to the Observation Post and told me what had happened. He looked dreadfully tired but was as keen as ever and although Col. Nevinson [ Lt. Col. Thomas St. Aubyn Barrett Lennard Nevinson ], the Brigade Commander, was anxious that I should relieve him, Houblon insisted on carrying on.

In the afternoon Stanford came up to the Observation Post and managed to get some good shooting at Germans in communications trenches. Towards evening Gilbert came up to relieve me and remain through the night.

2nd – On the following morning I again went up to the Observation Post. Our bombardment had practically stopped and there was very little to shoot at. In the German lines there was no sign of life and in “No Man’s Land” wounded were still crawling back to our trenches.

I had the opportunity of watching a very interesting bomber [ ? ] attack by the infantry on our right. Advancing from the trees just to the West of La Boiselle they went across No Man’s Land to the German trenches and then started bombing [ ? ] northwards. After they had advanced some 300 yards, sending up coloured lights to show their position, the trenches which had appeared lifeless, were now alive with Germans. Though hand grenades and stick-bombs were being exchanged heavily, there appeared to be no casualties. A little later the British officer seemed to be wounded and our people retired a little.

During the day I was told that the battery would be relieved that night, and in the afternoon an officer from the in-coming battery came up to see the Front.

For the best part of a fortnight we had been firing almost continuously day and night, and during all this time hardly received a dozen rounds in return. A few tear gas shells burst near the position, very irritating to the eyes but harmless unless they hit you. We had been issued with goggles against this but they were so uncomfortable that I could not keep mine on. In spite of reliefs right through the battery every one was dead tired.

The Battery Commander of the relieving battery happened to be an old friend of Houblon so the latter remained behind to talk to him.

3rd – It fell to my lot to take the guns out, and we finally left the position between 2 a.m. & 3 a.m., reaching the Wagon Lines, which had moved up to Albert, just as it was breaking dawn. Old Sgt. Major Stonard, who had not been to bed for nights, was simply splendid in keeping us supplied with ammunition. At the Wagon Lines we halted for about half an hour to give the men a chance to get some hot tea and make the final arrangements for our departure. It was quite light by the time we started on the main Albert – Amiens Road. Stanford had gone on to Brechencourt [ now Brehencourt ? ] (Amiens 1 F) to arrange billets. Beyond that we knew nothing of our destination. I had Gilbert and Frith with me. Shortly after leaving Albert, looking round, I saw the Sgt. Major turn up a side-road and wondered why. The poor old chap was fast asleep on a pile of stores.

4th – We arrived at Brechencourt at 8 a.m. and then heard we were only to be there four or five hours. After the horses had been watered and fed, and we had had breakfast, I walked round the lines. NCOs and men seemed to have fallen asleep wherever they happened to be. When “Boot & Saddle” sounded it meant waking up the greater part of the battery.

Houblon joined us shortly after leaving Brechencourt. From here we marched to Le Mesge about 12 miles West of Amiens (Amiens 1 A). It seemed a waste of time for we had to cross all the way back to Amiens the next day, to entrain once more at Longeau. Le Mesge was a long way from the line, quiet and pretty. We all thought we were in for a nice long rest after our strenuous time on the Somme, but it was not to be.

From Longeau we travelled to St. Pol (Amiens 2 E) arriving there very early the next morning. It was a cold & wet morning and the march a fairly long one through dreary country. We went through the coal-fields West of Bethune, long rows of miners’ cottages and nothing to relieve the atmosphere of the collieries. Our new billets were at Marles-les-Mines, nice and comfortable but the horse lines were very crowded. There we did a great deal of cleaning up, checking gun stores and getting new clothes for the men. Again we thought we were out for a rest, and we certainly got about eleven days. Little did we know then what those few days really meant. We were such a happy family party and all got on well together. Houblon was an ideal Battery Commander, scolding us when we neglected our work and putting us right when we did wrong through inexperience.

I suggested one day that, seeing we were in a coal mining area, it would be very interesting to visit one of the mines. Houblon fell in with my idea. We first went to the offices of the Company to interview the manager and obtain the necessary permission. This gentleman was most polite, first invited us to French cigarettes and then started asking us all sorts of questions. Were we miners? engineers? or had we any interests in coal mines? Houblon assured him he had always been a soldier, and I told him that I was endeavouring to be a farmer in Africa when the War started. This seemed to satisfy him and he proceeded to ring up one of the mines and make an appointment with his engineer there for the next day.

[ Davison then describes in detail his visit to the mines with Houblon ]

Riding back to the mess in Marles-les-Mines, we could not help laughing at the picture we had made, and related our experiences over lunch. Stanford, ever ready with his pencil, drew very amusing caricatures of us in our miner’s clothes, from our descriptions.

Houblon and I walked up to Brigade Headquarters an evening or two later to see if there were any orders or news about a move as there had been so many rumours. We found the Adjutant making out the orders for our departure the next morning at daybreak. He told us that we were going into action near Laventie (Haz 5 J) to cut the wire for the 61st Divisional Artillery. This Division had only recently arrived in France and their infantry battalions were going to make their first attack. We hurried back to our lines to warn the Sgt. Major, Q.M.S., etc so as to give them as much time as possible.

Houblon started off with the Battery Staff just before the guns, to reconnoitre the position. This was the beginning of the breaking up of our family party, for in a few days the whole battery was changed.

15th – We marched northwards, through Choques, Hinges, Lestrem to near Lagorgue [ now La Gorgue ] where we halted for a few hours in a field, and thought our Wagon Lines were to be here. We received a sudden order to move the wagons (the guns had gone into action) nearer to Laventie and in the hurry were obliged to leave our mascot, the black cat and her kittens, behind. We had brought them through all our travels, from the Somme Battle. If there is any luck in having a black cat, ours certainly changed when we deserted her in a farmhouse.

Now we went into a field just north of Laventie. The guns were first in action about a mile South-East of Laventie in the Rue de Bacquerot amongst the ruins of a farm called ‘Wangarie’ [ now ‘La Vangerie’ ]. There were practically no good positions, the best having been allotted to the 61st Divisional Artillery. Some of the guns were in the open and after the carefully entrenched gun-pits of the Somme, this seemed strange. From the Wagon Lines we started bringing up ammunition at once and had some 2000 rounds dumped, nearly all in one heap, behind the guns.

16th – When Houblon opened fire the next morning it was soon evident that the Germans had our position previously marked down. Sgt Hayes was the first to be killed and his body was brought down to the Wagon Lines and later buried in the military cemetery near Laventie. There were several other casualties that day and the dump of ammunition received one or two direct hits, setting it on fire. In trying to save some of the rounds Stanford picked up one which went off while he held it, leaving the empty case in his hand. He was dreadfully shaken and later that afternoon came down to the Wagon Line for a little rest.

In the evening I went up to the gun line with the ammunition to see if I could be of any use to Houblon. Everything was quiet now, the guns were still in position though one had been knocked out of action. Houblon had moved all the personnel two hundred yards to the right and the men were sleeping where they could. The subalterns were asleep in an old ruin while Houblon, looking fearfully tired, sat by candle-light working out the shooting programme for the next day. This was between 1am and 2am. He made me turn in and I have no idea how long he remained there working.

17th –The following morning we had orders to change our position to a field some 500 yards behind. This was another old 1914 position, just crumbling earthworks. All that day everybody worked hard at strengthening the positions and off-loading ammunition as it arrived from the Wagon Line and Divisional Ammunition Column. This time we dotted the ammunition about in little heaps of 200 rounds. When night came we were ready to start shooting again. Our mess was in a ruined house on the Le Flinque – Laventie road, and the room we had our meals in had only two walls (joining at the corner) and the floor of what had been the room above for a roof, the open side towards the Germans. This was about 100 yards behind the guns. The field the guns were in was surrounded by tall poplar trees, up to 60 or 70 feet, the guns being between the trees on our side.

18th – The next morning Gilbert went down to the front line and Houblon to the Observation Post. Stanford was in the Wagon Lines and Frith and I at the guns. We opened fire between 9am and 10am. After about the tenth round the first German shell came over, bursting just in front of the guns. The next hit a house, next to our Mess, in which trench mortar bombs had been stored. This round wounded two men but did not touch the bombs. The third round soon followed and cut down a big tree against which No. 2 gun-pit had been built. We were now registered and there was a pause on the German side. We had been firing all this time and got off a good many rounds at the wire. Soon the Germans started again and it became unpleasant. One or two more of these big trees were cut down and fell across our positions. I telephoned through to Houblon and told him what was happening. As he had almost finished he told me to stop, saying that he would put Gilbert in the Observation Post and return to the battery. His idea was to stop for a while, presumably to make the Germans think we had vacated, and finish off after lunch. He ordered me to keep away from the guns in case we both became casualties.

At about 2.30pm he started again. From our position we could clearly see the high trees from which the Germans were probably observing their fire and ours. I stood in the road behind the houses talking to the doctor who had his dressing station in one of the houses. After about twenty minutes I heard frantic whizzing noise in the air and one of our own 18-pounder rounds, complete, fell at my feet. I knew then that our position was being shelled again though Houblon was still firing. A few more rounds and then all was quiet. The next thing I saw was a stretcher being brought into the road by Frith and one of the gunners. On it lay Sgt King. Behind came Houblon, looking dreadfully white and limping slightly.

He looked at me and said very quietly “You will have to carry on, Chin [?], I am hit”. From what I was told afterwards he stood on top of the telephone dug-out or just to the side of it, conducting the firing as if it had been an ordinary drill. This was just behind No. 5 gun. He was wounded right across the thigh. He walked to the Field Dressing Station where the ambulances were but, I believe, nearly collapsed when he got there.

Later the only unwounded man from No. 5 told me he heard the shell coming and dived down a hole which turned out to be an old ammunition pit. The shell struck the gun on top of and right in the middle of the gun barrel, just in front of the gun-shield. No. 2 the range-setter and No. 3 the firer were both killed and Sgt King badly wounded. This was the round that also wounded Houblon.

When we had cleared up the position and taken the damaged gun away, we again set to work to strengthen the gun-pits, build a new telephone shelter and rig up a flash screen, for the attack was due to come off tomorrow, the 19th July. Everybody again worked hard and willingly till after dark, and not a round came over. I can only think that the Germans imagined we had vacated the position, at any rate till nightfall.

When everything had been done that could be done and we were ever more [ ? ] ready to start shooting, if necessary, I ordered tea and coffee for the men and being a lovely warm night they sat on the fallen trees, resting. Frith had gone over to the 33rd Battery to get a rest after the morning’s casualties and only Gilbert and I were left till we borrowed an officer from 33rd Battery (Major Packe’s).

It was now our turn to get a rest and a drink. We went to our house and began to make ourselves comfortable but had hardly started when there was a terrific crash and one (or two) German salvoes of heavy shells burst right on the position. Gilbert rushed out and I followed. A moment later there was a shout for stretchers. One man was badly hit in the legs and given first attention, Gilbert looking after him. Then I heard groans in a shell-hole and found Bombardier F. Kemshead who told me that he had been hit in the stomach. Poor fellow, the bit of shell had gone right through him. We carried him to the dressing station but he died very shortly afterwards. The 36th Battery also had casualties from this salvo. They were in the field next to us.

When the casualties had all been attended to we found ourselves in the 36th Battery’s Mess. They gave me the strongest whisky and soda I have ever had and I felt no effects whatever. It was nearly 11pm before Gilbert and I got any food and finally turned in.

19th – The next morning I went round to Brigade HQ to find out what was going to happen. As we were only lent to the 61st Division the two brigades were in one house and nobody could tell me anything, nor were they very interested in our batteries or our casualties. I eventually found out from our own adjutant that the attack would come off at 1pm. Col. Nevinson tried to cheer me up by saying that when all the 61st batteries opened fire the Germans would not have as much time for our position. I don’t think he quite realized what being ‘registered’ meant. I then hurried back to the battery to make the final preparations.

As a precaution I had all the officers’ kits and messing things moved from our ruin and left it to Frith to choose another place. The place he chose was a deep dry ditch about 600 yards away.

We had also dug a narrow V-shaped trench, to use as the telephone dug-out and Battery Commander’s command-post, behind Nos. 1 and 2 guns. We considered that there would be less to hit than where the other one was. We covered it first with corrugated iron, then heavy beams, earth and even rolls of wire netting. We could only make it barely 6ft deep on account of striking water. As it was there was always water at the bottom which now became thick mud. The gun detachments were reduced to the lowest minimum and kept what few remained in reserve. The gun-pits all had some sort of semi- splinter-proof screen at the back, and were all well stocked with ammunition. So at any rate, for some time, there was no necessity for anyone to be wandering about the position.

Punctually at 1pm we opened fire and for an hour or more received nothing back. All the batteries were now firing so, as the Colonel had said, the Germans had more to attend to, but they did not forget us and we were soon getting our share. Though still good his shooting was not up to his previous day’s form, probably because he expected to be attacked. I had received orders that if we were heavily shelled I was to evacuate the position. After the Germans had shelled us for some time the Colonel asked me on the telephone “when I was going back to my position”. It was rather a proud moment for the old battery when I told him that we had not yet left it. But we had to, a little later, for a short time. When we returned the dumps of ammunition, or some of them, were on fire and rounds flying in all directions. Gilbert did magnificent work putting out these fires. After this interval we continued firing till nearly midnight and then received the order “Cease fire”. We then heard that the attack had failed and that it would be attempted the following day which meant ordering heaps more ammunition. Fortunately this was all cancelled. The object of the attack was to prevent the Germans sending guns and troops down to the Somme Front. Judging from our experience the Corps certainly achieved its object.

There were no more killed or wounded that day but we had some very distressing cases of shell-shock, full grown and even elderly men who had been doing magnificent all through, crying like children and shaking like leaves. One young signaller came into the telephone trench for his tour of duty. He was, apparently, absolutely normal. After about ten minutes he turned to me and said “I believe I am going to give way, Sir”. I tried to do what I could for him, but he got worse. Gilbert was away trying to get me a cup of tea. All I could do was to send the remaining signaller away with this young fellow. This left me alone. The only light we had was a candle on a bit of wood stuck into the side of the trench. The telephone was similarly fixed. I had to keep my watch and map board handy to regulate the firing. Then the telephone rang, or rather buzzed. In my efforts to reach it I knocked over the candle which fell into the wet mud with a hiss and I was in darkness. Groping for the telephone the same thing happened, but without the hiss. Fortunately the telephonist returned at this moment.

Even these very unpleasant days had a humorous side, which was lucky. Gilbert, who was at the other end of the little trench all the time, and I, seemed to see something funny in nearly everything that happened, though I cannot account for this view of the situation.

We were told that we could clear our position of men as the 61st Divisional Artillery was covering the front. We now retired to our ditch where we found Frith who had prepared refreshments for the men and ourselves.

As was usual several ridiculous chits filtered through from Corps. One marked “Secret” informed us ‘how to adjust the nose-clip of the new gas-mask’ and another on ‘the care of india-rubber boots’. Though fully occupied with other matters these little pamphlets came as a blessing in disguise.

The following morning, as we were washing, a dud anti-aircraft shell fell from a great height and dropped quite near us, simply making a small round hole in the ground. I think this frightened us more than all the shells we had had in this position.

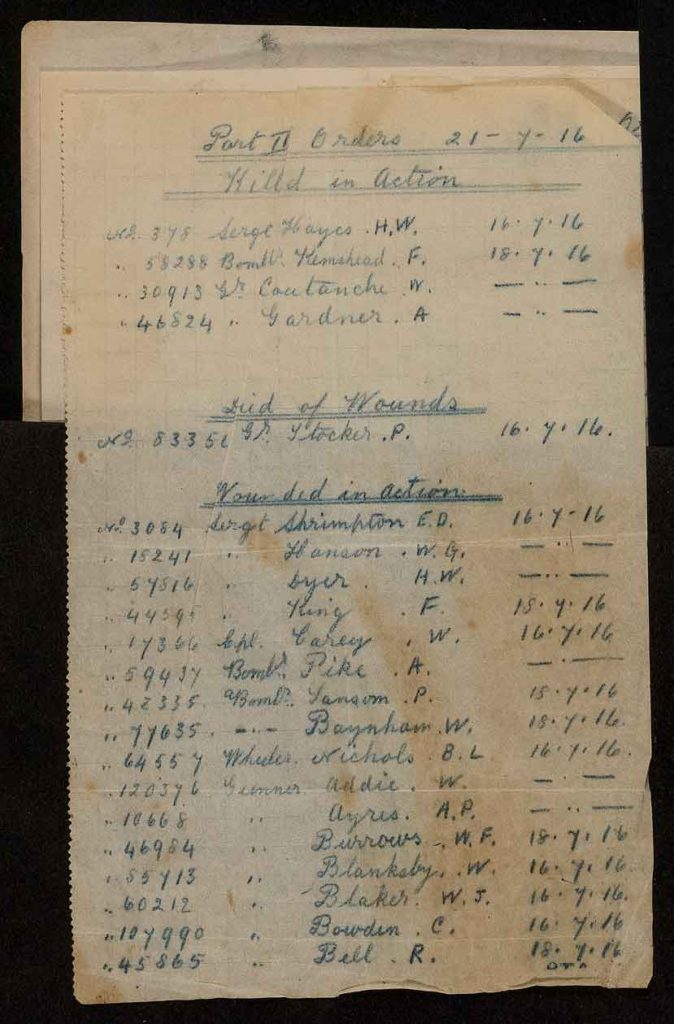

Part II Orders 21-7-16

Killed in Action

No. 378 Sgt Hayes H. W. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 58288 Bdr Kemshead F.H. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 30913 Gr Coutanche W. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 46824 Gr Gardner A. I. 18 · 7 · 16

Died of Wounds

No. 83356 Gr Stocker P. 16 · 7 · 16

Wounded in Action

No. 3084 Sgt Shrimpton E. D. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 15241 Sgt Hanson W. G. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 57816 Sgt Dyer H. W. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 44395 Sgt King F. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 17366 Cpl Carey W. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 599437 Bdr Pike A. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 42335 Bdr Sansom P. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 77635 Bdr Baynham W. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 64557 Whr Nichols B. L. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 120376 Gr Addie W. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 10668 Gr Ayres A. P. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 46984 Gr Burrows W. F. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 85713 Gr Blanksby W. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 60212 Gr Blaker W. J. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 107990 Gr Bowden C. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 45865 Gr Bell R. 18 · 7 · 1

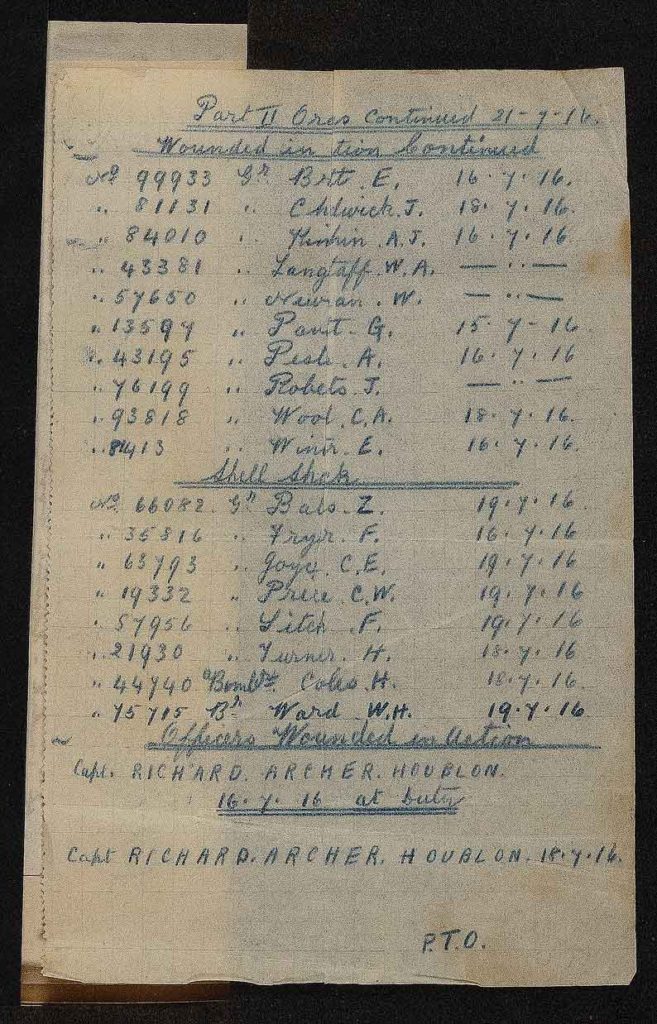

No. 99933 Gr Brett E. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 81131 Gr Chadwick J. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 84010 Gr Kinchin A. J. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 43381 Gr Langstaff W. A. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 57650 Gr Newman W. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 13597 Gr Pavitt G. 15 · 7 · 16

No. 43195 Gr Pester A. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 76199 Gr Roberts J. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 93818 Gr Wool C. A. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 81413 Gr Winter E. 16 · 7 · 16

Shell Shock

No. 66082 Gr Bales Z. 19 · 7 · 16.

No. 35816 Gr Fryer F. 16 · 7 · 16

No. 63793 Gr Joyce C. E. 19 · 7 · 16

No. 19332 Gr Price C. W. 19 · 7 · 16

No. 57956 Gr Sitch F. 19 · 7 · 16

No. 21930 Gr Turner H. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 44740 Bdr Coles H. 18 · 7 · 16

No. 75715 Bdr Ward W. H. 19 · 7 · 16

Officers Wounded in Action

Capt. RICHARD ARCHER HOUBLON 16 · 7 · 16 at Duty

Capt. RICHARD ARCHER HOUBLON 18 · 7 · 16

Captain T. H. Davison was promoted to Major on [ date? ].

While commanding 32nd Battery he was badly wounded in July 1917 when his dugout was destroyed by German heavy artillery; he subsequently received months of medical attention.

In October 1917 he was transferred to 8th Divisional Ammunition Column, becoming its commanding officer in July 1918. He suffered repeated problems with his health, spending time at 25 Field Ambulance and at a sanatorium.

He was awared the Military Cross on [ date? ] 1918 (London Gazette entry, 24th September 1918) ‘for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in charge of a patrol of six men. When about to rush an enemy post bombing was opened on them, wounding four of his patrol, one of whom was unable to move. He and an N.C.O stood up and beat down the fire, while the badly wounded man was being withdrawn. He then under heavy rifle and rifle-grenade fire assured himself that no more of his men were lying out wounded. He thus prevented the enemy from obtaining an identification’.

On demobilisation in February 1919 he took a post at the Repatriation Records Office in Winchester, as South African Liaison Officer.

In July 1919 he returned to Rhodesia, from where he had originally travelled to enlist in 1915.

This photo shows him with the other members of the office in Winchester between February and July 1919.

Notes:

Personal war diary of Capt. T. H. Davison – Royal Artillery Museum (papers of Major T. H. Davison M.C.) via The Ogilby Muster

Advice and assistance – Charlie (‘charlie962’) of The Great War (1914-1918) Forum