A Great War story - Gunner William Baynham

1915

William enlisted at Walsall on 13th April 1915, a few weeks before his 18th birthday; his Attestation shows his age as 19, which was the requirement at the time.

The form also shows that his was a Short Service Attestation – 3 years with the Colours and 9 years in the Reserve.

At the time he was living at home and working as a plater.

He was passed fit for service in the Royal Field Artillery by the Recruiting Officer and described as being five feet nine and three quarter inches tall, with brown hair, grey eyes and a fresh complexion.

He signed up with two other local men, Willam Millett and George Cartwright and it appears that the stories of these three Walsall Pals may be intertwined – they all joined the Royal Field Artillery and all three men survived the war.

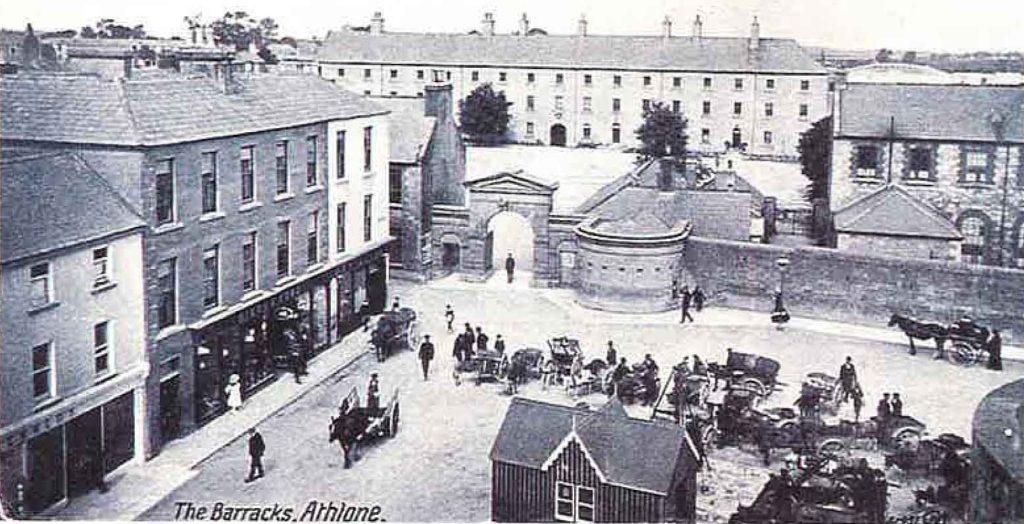

The day after enlisting, William was posted to No. 5 Depot, Royal Field Artillery at Athlone in Ireland; there he was allocated Number 77635 and did his basic training as a member of 5B Reserve Brigade.

On 28th August 1915 he was transferred to 4A Reserve Brigade at Woolwich prior to being sent overseas, as was standard at the time.

His posting to the British Expeditionary Force, as a reinforcement gunner, came on 25th September and he landed at (Le) Havre in France the following day. Initially he went to the Base Depot there, to await a unit posting.

This came on 29th with a posting to the Ammunition Column of the 8th Division which was billeted in and around Doulieu.

According to the 8th DAC War Diary, apart from a couple of nights away for manouuvres with the rest of 8th Division, it remained there until April 1916 when it moved to Bavelincourt, near Albert.

1916

After serving with the 8th DAC for five months, he joined 32nd Battery, part of 33rd Brigade (still within 8th Division), on 1st March 1916 at Fleurbaix.

He was now the gun layer in an 18-pounder gun crew.

His Battery Commander was Captain Richard Archer Houblon, a regular soldier, with Captain Thomas Henry Davison, a reservist, second-in-command; the Brigade Commander was Lieutenant Colonel Thomas St. Aubyn Barrett Lennard Nevinson.

The Brigade left Fleurbaix on 26th March and by 7th April was in positions near Albert to begin preparations for the Somme Offensive.

Together with ‘O’ Battery RHA and 55th Howitzer Battery it formed the Right Artillery Group of the 8th Division, having on its right the 21st Division and on its left the Left Group (which Div?). By 10th/11th April it was being bombarded by enemy heavy artillery and gas shells … A day-by-day account of this move to Albert and how the Brigade retailiated to hostile fire can be found in the 33rd Brigade War Diary for this period.

In early May the batteries moved their positions and 33rd Brigade was strengthened and became a ‘mixed brigade’ by the addition of 55th Howitzer Battery.

On 23rd June, William was promoted to Acting Bombardier.

On 24th June, starting at dawn, the 18-pounder guns began the task of cutting enemy wire to prepare the way for the planned infantry assault across No Man’s Land; this continued each day until the end of the month. There were also periodical bombardments of the enemy’s trenches during the day, which intensified towards the end of the month, and at night roads and communication trenches were searched with shrapnel. There was little retaliation from the enemy until 29th.

1st July 1916 was the first day of the Battle of the Somme. Lt. Col. Nevinson’s entries in his Brigade War Diary record what happened in his sector:

“06.25 – Bombardment opened. The morning was hazy and this combined with the discharge of smoke on the left made a clear view of operations impossible until later on. Shortly after opening our bombardment the enemy bombarded both our front and support lines with 77mm, 105mm and 150mm, some lachrymatory shells being fired”.

“07.18 – The Middlesex, Devon Regt, Lincolns and Berks first waves went over followed by others at short intervals”.

“07.29 – Heavy hostile machine gun fire from several points, including a bank and a trench. There was only a slight 77mm barrage on No Mans Land. The first two waves of the Devons were checked on the German parapet and the succeeding waves were mown down by machine gun fire in crossing No Mans Land …”

There is a detailed account of the remainder of the first day and days two to four of the Somme Offensive in Nevinson’s 33rd Brigade War Diary and Davison’s personal diary records what he saw from an observation post. There is no mention of any casualties in the brigade, probably because the barrage from British heavy artillery (further back from the Front) in the days leading up to the offensive had been so intense that there was relatively little German retaliation.

On the nights of 3rd and 4th July the brigade was relieved by batteries of the 12th Division and marched to rest billets in 1st Army Reserve at Marle-les-Mignes, which they reached on 7th July. Meanwhile, for the first few days of July, William Millett (one of my grandfather’s ‘Walsall Pals’) was camped with the rest of his unit (112 Brigade R.F.A.) in the woods at Vadencourt awaiting orders for action while its officers went forward to look at the firing line. At this point in the war, the two Williams might have been less than 3 miles apart …

On 14th July, after a week’s rest, 33rd brigade marched to new positions near Laventie and began wire-cutting on a front of about 800 yards. Although “a considerable amount of the wire was cut”, unfortunately the 18-pounder batteries had come into hastily constructed positions well in view of the Aubers Ridge, with the result that when fire was opened on morning of 16th the 32nd and 36th Batteries were heavily shelled, resulting in many casualties. On 16th, 32nd Battery had 1 NCO killed and 18 NCOs and men wounded, 36th Battery had 4 NCOs and men killed and 4 wounded.

So, on the evening of 16th, the 32nd and 36th Batteries moved out to new positions where they constructed new emplacements and continued wire-cutting on 17th.

This photograph is illustrative of a well-constructed gun position; it was taken by H. D. Girdwood, on 4th August 1915. He said that the gun was at Lavantie, firing on a German position, but this may be incorrect as many of his photographs were staged for propaganda purposes. It is interesting to see that it has several of the features of the ideal gun pit devised by Houblon.

On 18th, shortly after fire had been opened, the 32nd and 36th Batteries were again shelled, with further casualties: 32nd Battery lost 3 men killed, 9 wounded (including Capt. Archer Houblon) and a further 3 suffering from shell shock. My grandfather was one of the 8 other ranks wounded that day – he suffered wounds to his head and right shoulder, reported as ‘severe’. Capt. Davison, who took over command of 32nd battery when Houblon was wounded, recounts his experience of these events at Laventie in his personal war diary.

So while the Brigade continued wire cutting and took part in more offensive operations, William was admitted to No.95 Field Ambulance, probably at the Advanced Dressing Station in La Flinque or the Main Dressing Station in Vieille Chapelle.

On 21st July, he was admitted to No.14 General Hospital, at Wimereux. He was one of 202 other ranks admitted on that day, according to its war diary; the diary also shows that capacity had had to be increased significantly after the first week of the Somme offensive, expanding the hospital with an additional 4 marquees and 2 operating tents and increasing the number of fully equipped beds to 957 (but at the same time lamenting a shortage of personnel, especially officers and nursing staff).

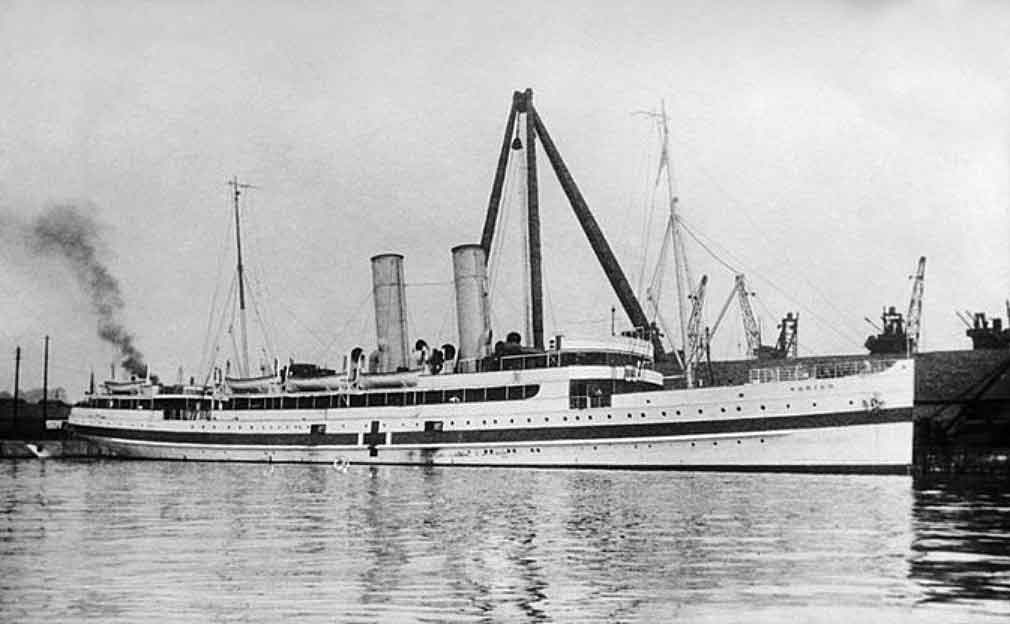

He was taken back to England on the Hospital Ship ‘St Denis’, probably crossing from Boulogne on 22nd July (see Note 1 ‘Return to UK – 1916‘, below).

On arrival he was posted to 5C Reserve Brigade; apparently this was standard practice for anyone who had been repatriated and needing hospital treatment as it meant that a place at 5C Reserve Brigade would have been secured on discharge from hospital. As yet no records have emerged to reveal where else William was hospitalised or convalesced.

However, his record shows that on 14th October he was sent to the Command Depot at Ripon for further convalescence, because by this time 5C Reserve Brigade was overwhelmed and would have had no place for him (Command Depots had been formed in November 1915 and the Ripon site included a huge military hospital with 670 beds, erected in North Camp).

On 4th November he was posted to 7th Reserve Battery, 2nd Reserve Brigade at Bettisfield Park situated between Whitchurch and Ellesmere in Shropshire; by now Reserve Batteries could send men directly to ports of embarkation rather than via 4A Reserve Brigade at Woolwich (as had happened the previous year, when he was posted to 4A en route to France in September 1915).

He went overseas again on 9th December and re-joined the Expeditionary Force at Base Depot in France (presumably at Havre).

On 16th December, he was posted from Base to 19th Divisional Ammunition Column which, according to the 19th DAC War Diary, was in billets at Hem where it had just completed a 7-day rest period.

A couple of weeks later, on 29th December 1916, he was posted to 86th Brigade (also part of 19th Division); it’s unclear whether he joined on that date or on 24th January, when the brigade war diary notes that “personnel, horses and vehicles from 19th Divisional Ammunition Column joined”, following a re-organisation of the brigade. He joined ‘A’ Battery, which in December was in billets at Occoches and in January was near Hebuterne.

1917

In mid February 1917 his battery, with ‘B’ and ‘D’ Batteries, moved into new positions near Serre, to engage the enemy prior to an infantry attack on Knife & Fork trenches north of Puisieux.

In early March they moved again, to two different positions near Puisieux for wire-cutting duties on the Arnum and Bucquoy trenches which they completed successfully. However, the infantry attack here was unsuccessful and the gunners suffered heavy enemy shelling until the hostile fire was “quietened by the heavies”. The Germans then evacuated Bucquoy, Achiet-le-Grand and sundry other villages which meant that the brigade’s guns were out of range, so on 21st March the brigade was withdrawn.

On 27th March it was sent to new positions just north of Arras.

Here they engaged in more day-time wire-cutting, in conjunction with medium and heavy trench mortars as well as howitzers from 311 Brigade RFA; they managed to keep open the gaps in the wire by firing at night. They then put down barrage shelling prior to a successful attack by the infantry of the Third Army east of Arras on 9th April, as part of the wider Battle of Arras.

The success of the infantry attack meant that the batteries could be moved 1,000 yards closer to the front, but the brigade’s officers suffered such heavy casualties that between 2nd and 10th April all battery commanders had been either killed or wounded. Despite this, the brigade was still able to keep firing day and night.

What the war diary shows is that near Gavrelle the batteries continued to fire around the clock for the next two weeks, with little respite. It records that by 14th April, the enemy was reported to be falling back on the Gavrelle-Oppy line of trenches West of Gavrelle. Infantry patrols then pushed on through Bailleul [ now Bailleul-Sir-Berthoult ] and forward to within 300 yards of those trenches but were held up by machine gun fire from Gavrelle, so the 18-pounder batteries moved forward into new positions and started wire cutting on the line.

This continued until the 18th when wind conditions and the frontal nature of their target made wire-cutting from their positions difficult, so a section of D Battery was moved to take the wire in enfilade with 106 Fuze shells while the remainder kept up their fire on the Eastern and North-Eastern approaches to Gavrelle. On the 20th, D Battery started wire-cutting with good results, while the remaining guns registered enemy trenches during the day and at night fired on the approaches again. The following day, D Battery continued wire cutting and the other 18-pounders rehearsed an SOS Barrage and during the night they kept up fire on the approaches and on the wire, to keep the gaps open. On the 22nd, all batteries were engaged in wire cutting throughout the day and kept the gaps under fire throughout the night.

On 23rd, the 63rd (RN) Infantry Division attacked Gavrelle and achieved all of its objectives; seven enemy counter-attacks were attempted and failed. The guns kept up fire on the back areas during the night to prevent the enemy massing for another counter-attack and the following day took on ‘opportunity tagets’ while the heavies bombarded Gavrelle; the back areas were again kept under fire during the night. The 25th saw little activity – small parties of the enemy were fired upon during the day and intermittent fire was kept up throughout the night on roads and tracks in the back areas. On 26th all batteries continued firing at opportunity targets during the day; during the night they started digging forward positions in the valley west of Gavrelle, while the Brigade Ammunition Column and Wagon Lines brought forward more ammunition.

The war diary certainly gives the impression that there was non-stop activity, day and night, until the 27th when the men were finally allowed to rest during the day, but that night they had to finish their new positions and move into them; further quantities of ammunition were also brought up.

At 4·25 am on the morning of 28th, 63rd Division made an attack on the Oppy-Arleux line and attained all its objectives, but, owing to heavy counter attacks, ground near Oppy and North-East Gavrelle was not held; however, the important position of the Mill at Gavrelle was captured and was held.

During the day of the 29th, everything was quiet – the brigade did not fire, due to the exposed positions of its batteries. For the same reason there was very little firing on 30th, but that night B Battery had to move its position as it got ‘ shelled out’.

During the month of April 1917, the brigade lost 4 officers and 12 men killed, plus 8 officers and 23 men wounded, mostly from B and D Batteries.

After replacements arrived at the beginning of May, the brigade moved to new positions near the river at Athies (to enable the guns to bring in enfilade fire on their targets) and dug in. After a couple of quiet days, punctured only by an SOS Barrage from A and C Batteries, 17th Corps attacked the cemetery, chemical works and buildings North of Doouai in the evening of 10th May and attained their objectives, capturing about 300 prisoners; 86th Brigade covered front of 311th Brigade during these operations. A couple of days later, the 4th & 117th Divisions made an early-moring attack on Roeux, the cemetery and trenches in the vicinity; again 86th Brigade took over the front of 311th Brigade during the attack.

The next day was relatively quiet and on 14th May, the brigade began to move out – first to its Wagon Lines near Anzin [ now Anzin-Saint-Aubin ], to prepare for the march to a new position near Ypres. Overnight it was billeted at Hermin, then Ames and finally Guarbecque which it reached on 17th. On 20th it received orders to march to Morbecque that afternoon. The next day it marched into the 2nd Army Area and occupied billets in Watou, where it was transferred from XIII Corps to X Corps and attached to the 47th Division.

Over the next few days and nights the brigade took up its new positions near Ypres and dug in, in preparation for the Battle of Messines Ridge. Despite suffering heavy casualties to its wagon lines, as well as a gas attack, it had managed to bring ammunition up to the new positions during the nights of 22nd to 28th May and then engaged in wire-cutting, around-the-clock general bombardment of enemy areas and practice barrages, ready for the assault. Bombardment of the enemy positions “increased daily in violence” in the early days of June 1917 and the 86th Brigade War Diary notes the famous detonation of mines early on the morning of the 7th June prior to the successful attack and capture of the ridge.

After the battle the front became relatively quiet, but on 12th June William was wounded again, this time with a shrapnel wound to the right groin; he was admitted the same day to No. 17 Casualty Clearing Station at Remy Siding, Lijssenthoek.

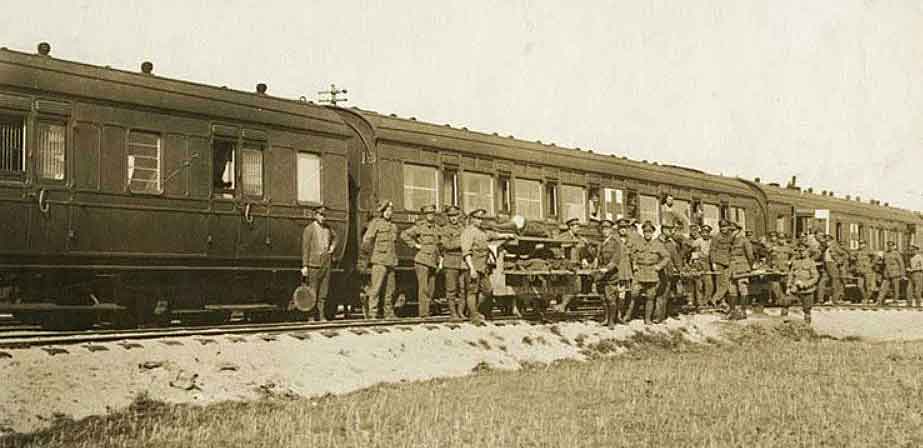

The 17 CCS War Diary for 13th June records that it “began receiving patients at 8pm last evening 12/6/17 and closed about 2pm today” and that “Ambulance Train No. 18 took away 42 lying and 47 sitting, all wounded”. It appears that this was the train that took William to Etaples (see Note 2 ‘Return to UK – 1917’, below). According to its war diary, the train arrived at Lijssenthoek (from Mendinghem) at 12:35 and started to load 482 patients at 12:50; it finished loading at 14:25 when it left for Etaples, with a total of 550 men on board. It arrived at Etaples at 20:00 and “started unloading at once”, then drew rations; it finished unloading at 21:05 and “received orders to garage”.

At Etaples, he was admitted to No.1 Canadian General Hospital as one of the 221 new patients who were admitted on 13th June, according to its war diary. He probably stayed there just a couple of days, being discharged on 15th or possibly 16th if there was an early-morning ambulance train to take him to Calais.

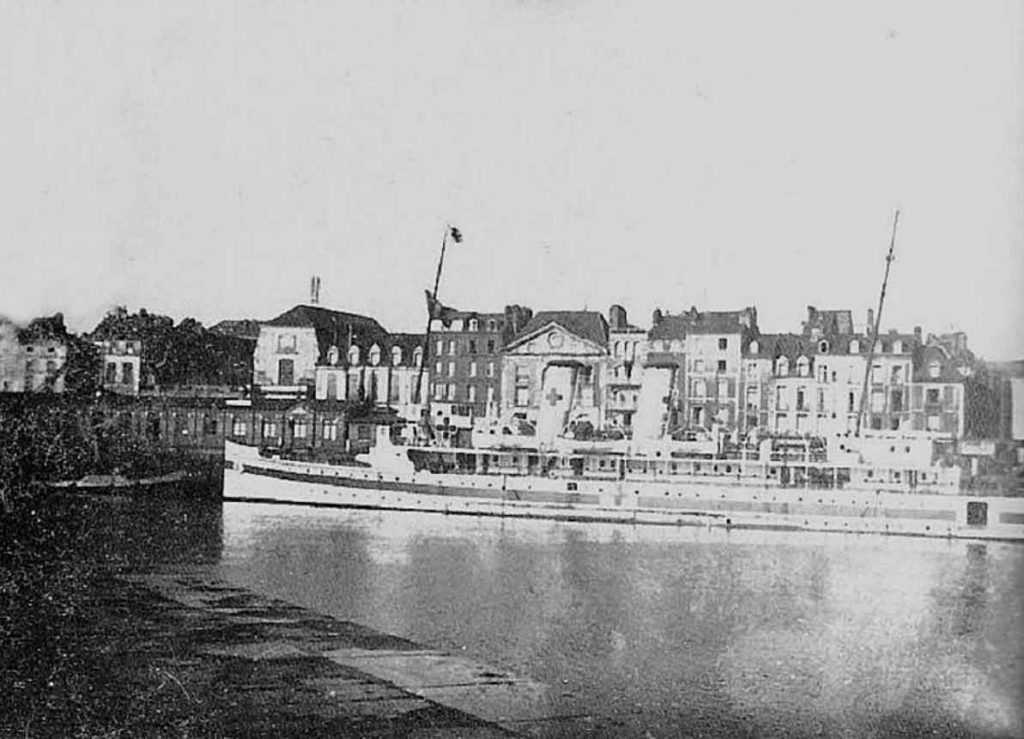

He was brought home on the HS Stad Antwerpen on 16th June 1917.

The hospital ship’s war diary for that day records that embarkation at 09:05 included 9 officers, 141 other ranks and 20 Germans “in cots”, 6 officers and 101 other ranks “sitting” – a total of 277 men (the diarist mis-calculates the total as 227). The ship left Calais at 12:45 and by 14:20 was “alongside at Dover” where it “disembarked all patients”. It appears that there was no escort ship for this crossing, unlike on most other days.

On his return to England William was posted to Clearing Office (BEF, France) at Woolwich, which signifies his arrival back home as a casualty and would have been an administrative posting whilst he was in hospital; he was being paid as a Lance Bombadier. As yet no records have emerged to reveal where William was hospitalised or convalesced.

On 11th August he was posted to 4 Reserve Brigade at Woolwich.

Twice wounded, he was entitled to wear two wound stripes on his lower left sleeve which are just visible in this photograph of him (which must have been taken at some time after June 1917, possibly at Woolwich). Above them is his Good Conduct Stripe, for completing two years’ service with good conduct. Also visible, on his upper right sleeve is his Gun Layer’s badge.

1918

After William’s Occupational Index Card was completed, on 18th February he was once again posted to the British Expeditionary Force in France and his service record shows his rank on being posted overseas was verified as ‘Gunner, Paid Lance Bombardier’.

Almost immediately upon arrival at Havre, on 20th February he was admitted to No. 39 General Hospital there as a patient whose illness was ‘not yet diagnosed’; he remained in hospital until 26th May when he was discharged back to Base Depot, Havre having recovered from Scabies.

However, in less than three weeks he was back in the same hospital on 13th June, again being admitted with an undiagnosed illness; he was there for a month before being discharged (presumably back to Base again) on 15th July having recovered from Impetigo.

His next posting was to 1st Army Reinforcement Camp.

From there, on 13th September 1918, he was posted to 24th Divisional Ammunition Column which at that time was at Marquaffles Farm near Bouvigny-Boyeffles, between Gouy-Servins and Aix-Noulette (West of Lens) where it had been since early May.

Its War Diary reveals that it had been involved in a variety of tasks, including lots of salvage work. It was busy moving ammunition between dumps, but also loaning out horses and carts and heavier transport to carry macadam for road building in the area.

Perhaps William was no longer fit enought to be part of a gun crew on the front and was employed here for his horse-handling skills? In any event, he was promoted to Bombadier on 13th November while still with 24 DAC.

1919

The next entry in his service record is after the end of the war – on 20th January 1919 he was granted ‘Leave to UK with Ration Allowance’, until 3rd February when he returned once more to France. Presumably he re-joined 24 DAC.

He left France for the last time on 22nd June when he embarked for UK from the Boulogne Dispersal Area.

For demobilisation he was sent to Clipstone Camp, the Dispersal Station / Demobilization Discharge Centre closest to his home as it covered Staffordshire, Derbyshire, and Nottinghamshire.

On 21st July 1919 he was transferred to Section B Army Reserve; he was given his new number 1011851 in 1920.

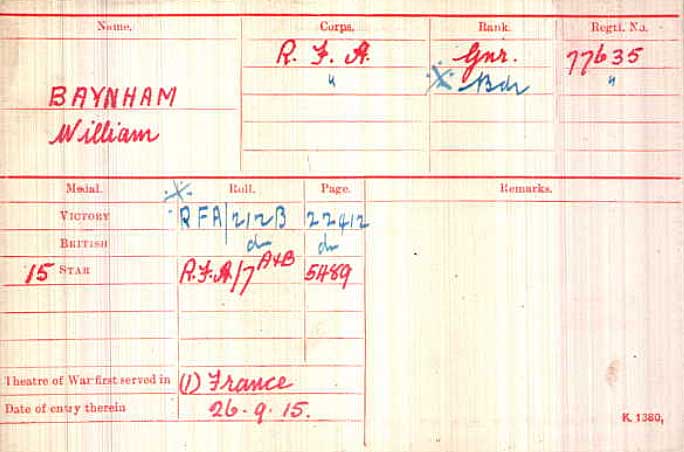

He was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal – all three medals are shown on his Medal Index Card.

1921

During a period of industrial unrest in the Spring of 1921, as a reservist he was recalled to the colours on 12th April and stationed at No. 1 Depot in Newcastle Upon Tyne until 3rd June, when he was again demobilised and transferred back to Section B Army Reserve.

1927 – 1938

On 3rd March 1927 he signed up for another 4 years as a reservist, from 13th April 1927 when he was confirmed as a Bombadier and transferred to Section D Army Reserve.

On 21st October 1930 he signed up again for a further 4 years, from 13th April 1931 when he was again confirmed as a Bombardier in Section D Army Reserve.

He signed up one last time on 17th December 1934 for a further period from 13th April 1935 to 12th April 1938, again as a Bombardier in Section D Army Reserve.

He was finally ‘discharged on termination of engagement’ on 12th April 1938.

Notes:

William’s service record shows that he was wounded in action on 18th July 1916 at Laventie and on the same day admitted to No.95 Field Ambulance. On 21st July, he was admitted to No.14 General Hospital at Wimereux (HA 1139) and returned to England per Hospital Ship ‘St Denis’.

The war diary of 95 Field Ambulance has no details of patients, but does show that on 18th July the Main Dressing Station was at Vielle Chapelle, with the Advanced Dressing Station at La Flinque.

The war diary of No.14 General Hospital at Wimereux simply records for Other Ranks 202 admissions (and 210 evacuations) for 21st July and (161 admissions and) 113 evacuations for 22nd; Hospital Admissions List 1139 is not available.

The war diary of Hospital Ship ‘St Denis’ is missing July 1917, but there is evidence of a crossing from Boulogne to England on 22nd July in the service records of Walter Robert Hayes (see https://birtwistlewiki.com) and a Sgt. Mair (see ‘Fromelles 1916’ by Paul Cobb). The ship was built in 1908 as ‘Munich’ for the Great Eastern Railway and sailed on the Harwich – Hook of Holland crossing. During WW1 she was requisitioned by the Admiralty and converted into a hospital ship with 231 berths.

As yet, no records have emerged to show which ambulance train took him from Wimereux to Boulogne.

William’s service record shows that he was wounded in action on 12th June 1917 and admitted to No.17 Casualty Clearing Station, Lijssenthoek on the same day. Next he was admitted to No.1 Canadian General Hospital and then sent to England per per Hospital Ship ‘Stad Antwerpen’ on 16th June.

The 17 CCS War Diary records that on 13th June it “began receiving patients at 8pm last evening 12/6/17 and closed about 2pm today”, so William was probably one of those patients received at Remy Siding.

It also records details of two ambulance trains leaving Remy for Etaples during this period – on 12th, “Ambulance Train No. 23 arrived about 12.45pm and took away 3 lying cases only” and on 13th “Ambulance Train No. 18 took away 42 lying and 47 sitting, all wounded”. The only other trains mentioned in the diary both went to Boulogne, so can be discounted (on 14th, “No. 28 Ambulance Train took away this morning 43 lying and 48 sitting, and 4 Germans lying” and also “No. 14 Ambulance Train arrived here today”; on 15th, “No. 14 Ambulance Train left today at 12 noon and took away lying 31, sitting 51, also 1 German lying”).

The war diary of No.1 Canadian General Hospital in Etaples for the relevant period records no admissions for 12th June, so it is unlikely that he would have travelled on Ambulance Train No. 23; new patients were admitted to the hospital on 13th (221), 14th (226) and 15th (205), so William was most likely admitted on 13th, arriving from Remy aboard Ambulance Train No. 18.

If William was admitted to No.1 Canadian General Hospital on 13th June, he would have been there for just a couple of days, as he was on board a ship at Calais by the morning of 16th June.

From Etaples he would have travelled on another ambulance train to Calais, to meet that ship. The hospital’s war diary records that existing patients were discharged on 14th (47), 15th (35) and 16th (16), so he could have been discharged on any of these days, but most likely 15th or perhaps 16th if there was an early-morning ambulance train from Etaples to Calais.

As yet, no records have emerged to show which ambulance train took him from Etaples to Calais.

Army Service Record – Historical Disclosures, Army Personnel Centre, Glasgow

War Diaries of the following units – The National Archives

- 8th, 19th & 24th Divisional Ammunition Columns, Royal Field Artillery

- 33rd & 86th Brigades, Royal Field Artillery

- No. 95 Field Ambulance

- No. 17 Casualty Clearing Station

- No. 14 General & No. 1 Canadian General Hospitals

- Nos. 14, 18, 23 & 28 Ambulance Trains

- Hospital Ships St. Denis & Stad Antwerpen

Photographs –

- Barracks, Athlone – Athlone Library

- Casualty Clearing Station & Ambulance Train – Northumbrian Gunner

- Hospital Ships – Dover Ferry Photos

- William in uniform – family

- Remainder – WikiMedia Commons

Advice and assistance – various members of The Great War (1914-1918) Forum in particular David Porter, Graeme Clarke, Max D, ‘sadbrewer’, ‘tullybrone’, ‘wmfinch’, ‘awjdthumper’, Craig (Admin) and Charlie (‘charlie962’)